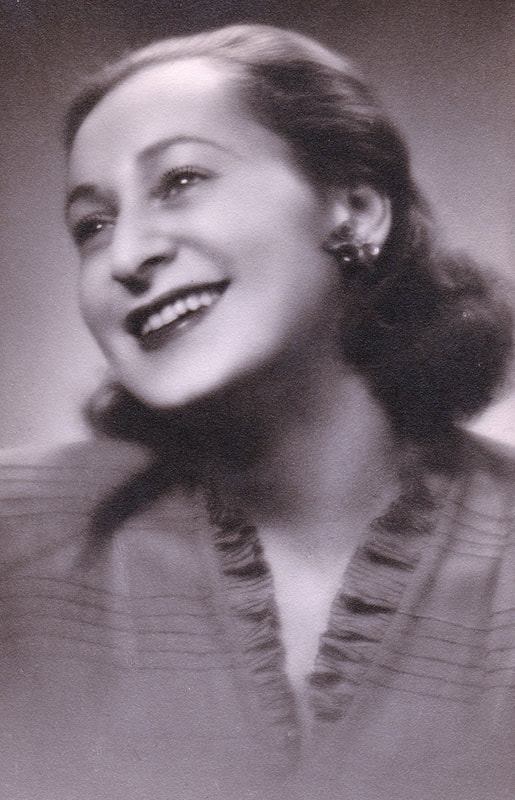

Survivor - Wife to Soldier and War Hero - Mother - Nurturer - Matriarch - Grande Dame

16 December 1920 - 10 April 2020

Beautiful, Vulnerable, Complex

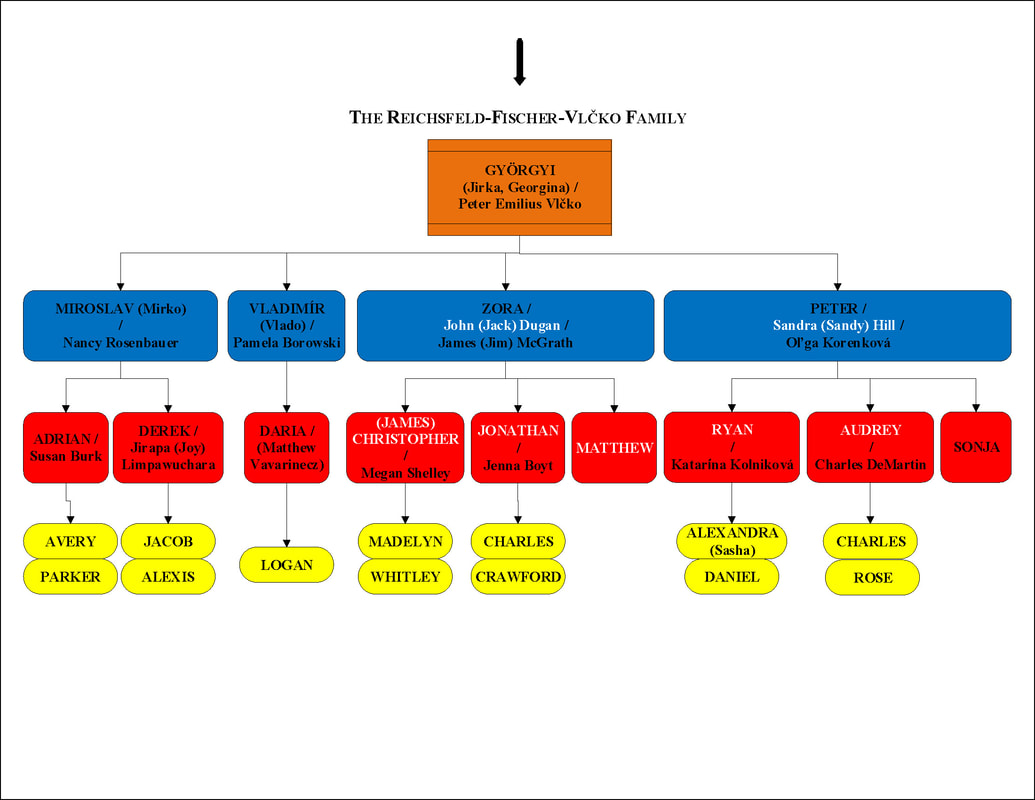

Her's is a story in its own right and a fitting complement to General Peter Vlcko's story. The above descriptors become self-evident throughout her testimony.

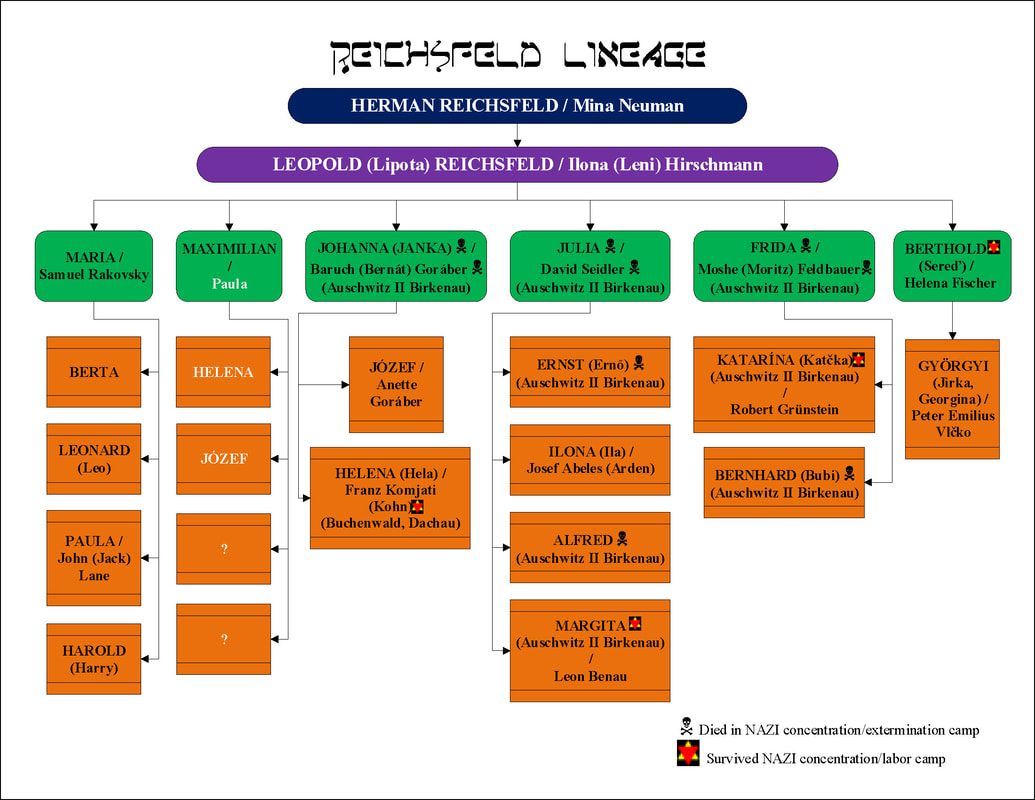

We begin with a short introduction to Georgina's ancestors.

We begin with a short introduction to Georgina's ancestors.

THE FISHERS

|

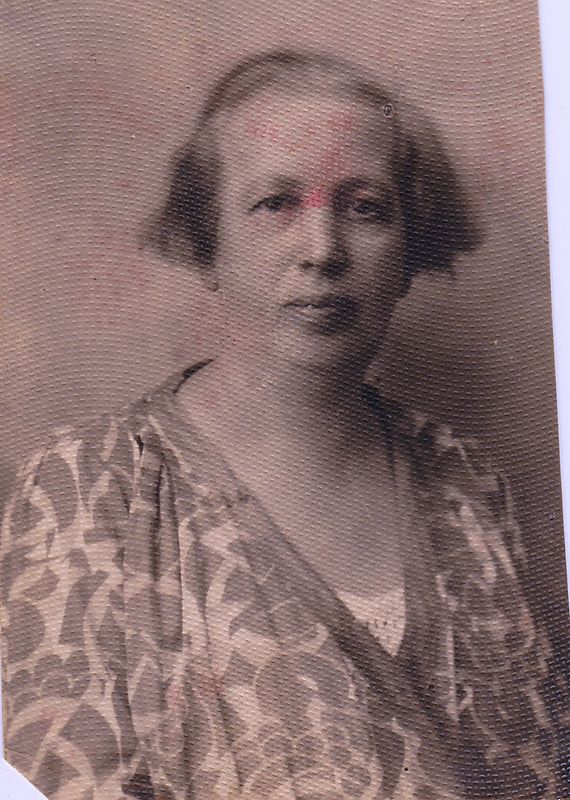

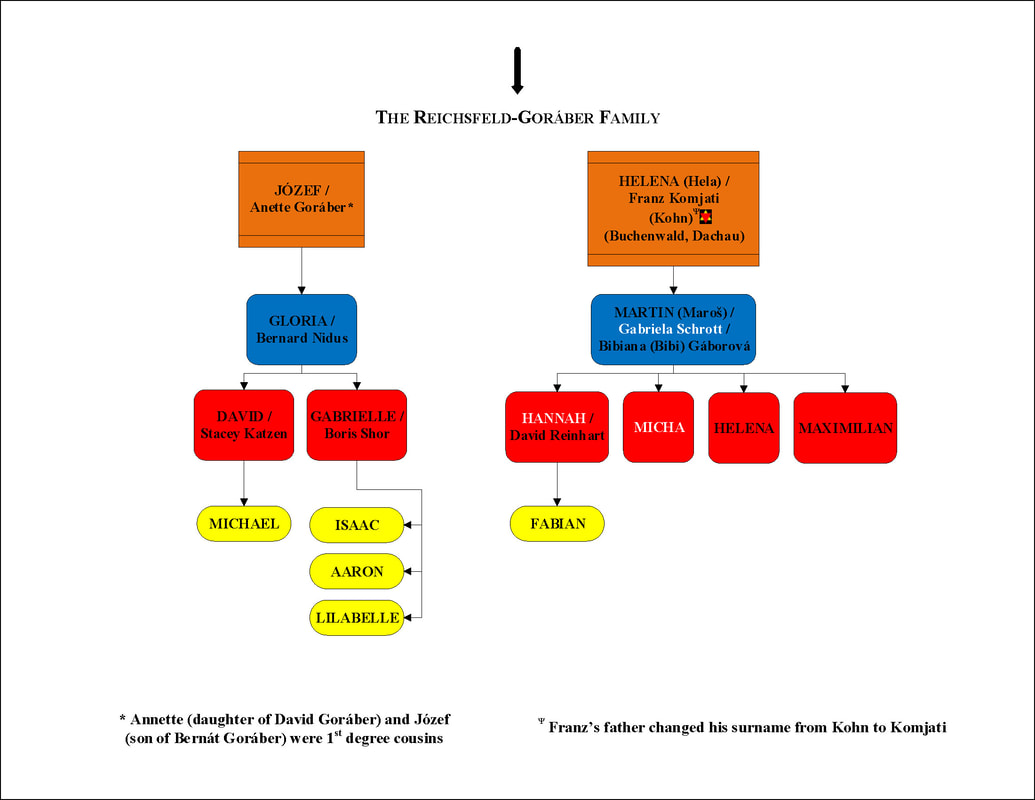

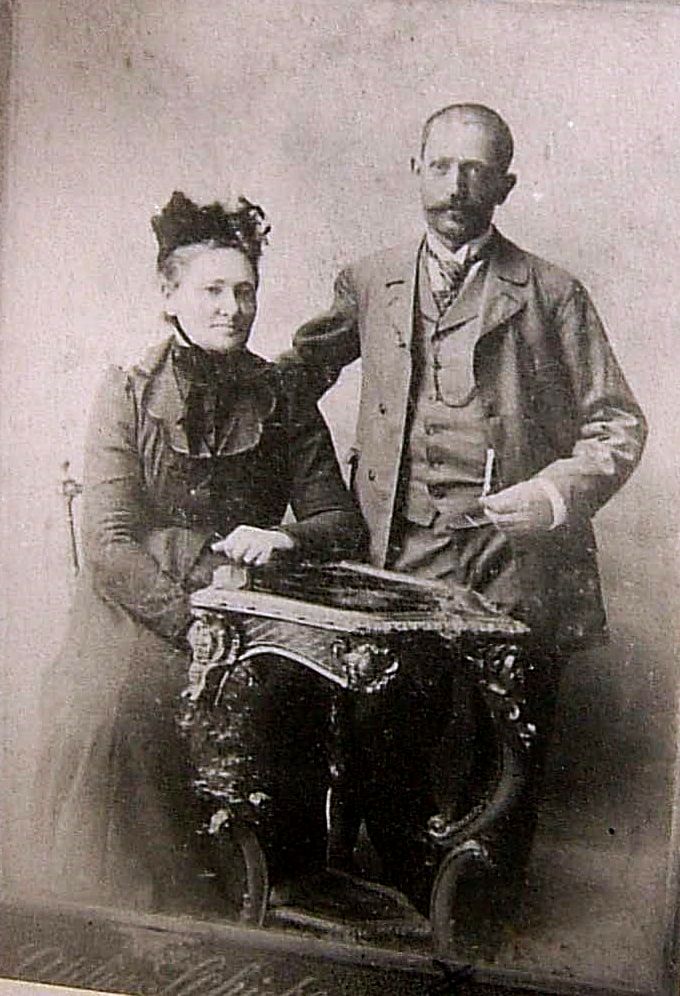

c. late 19th century Budapest Austro-Hungary, Georgina's maternal grandparents Jákób and Jozefina (née Österreicher) Fischer. A branch of the Österreichers in Austria settled in Transylvania (modern-day Romania) while the Fischers lived in Hungary. Jákób and Jozefina Fischer owned a bakery in Budapest whose biggest customer was the Austro-Hungarian Army. Jákób Fischer suffered from diabetes mellitus and died before Georgina was born.

|

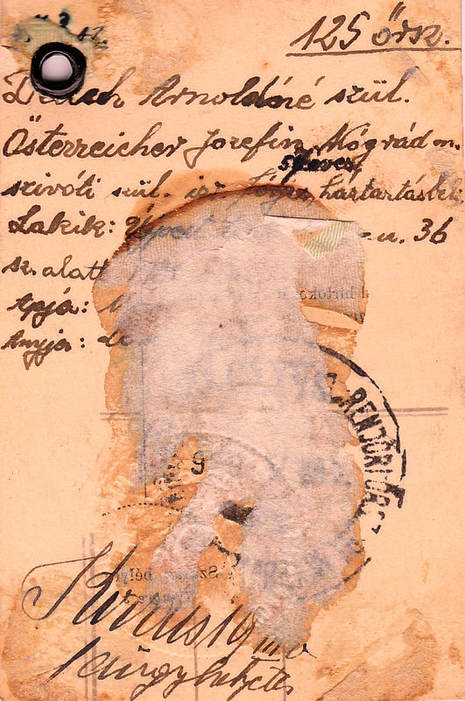

The above picture of Jozefina Fischer was taken from her official identification card. For reasons that remain unclear, she used the false name Decélsseh Arnoldóré, although the back of the photograph states her birth name was Jozefina Österreicher born in the Austro-Hungarian city of Nagy-Várad (modern day Oradea, Transylvania).

THE REICHSFELDS

|

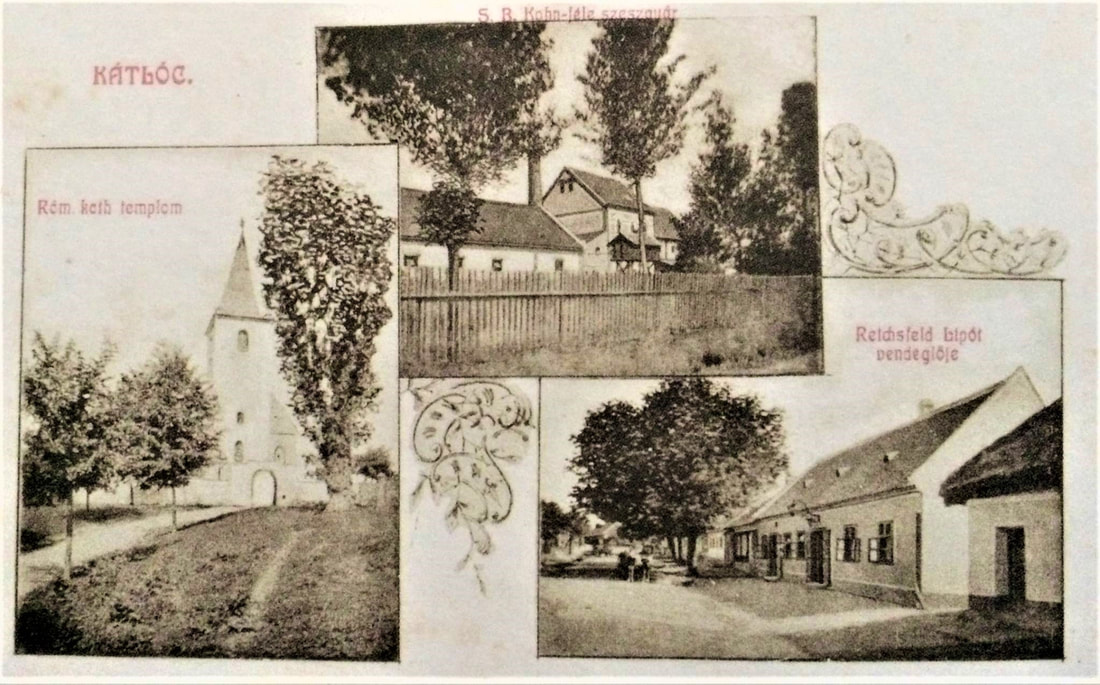

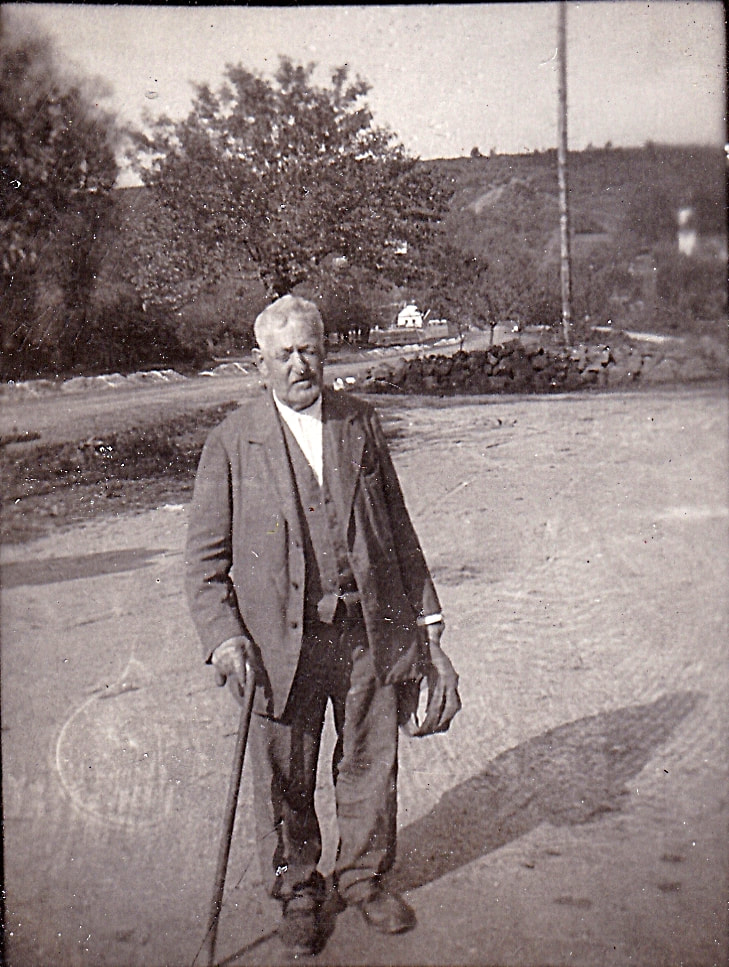

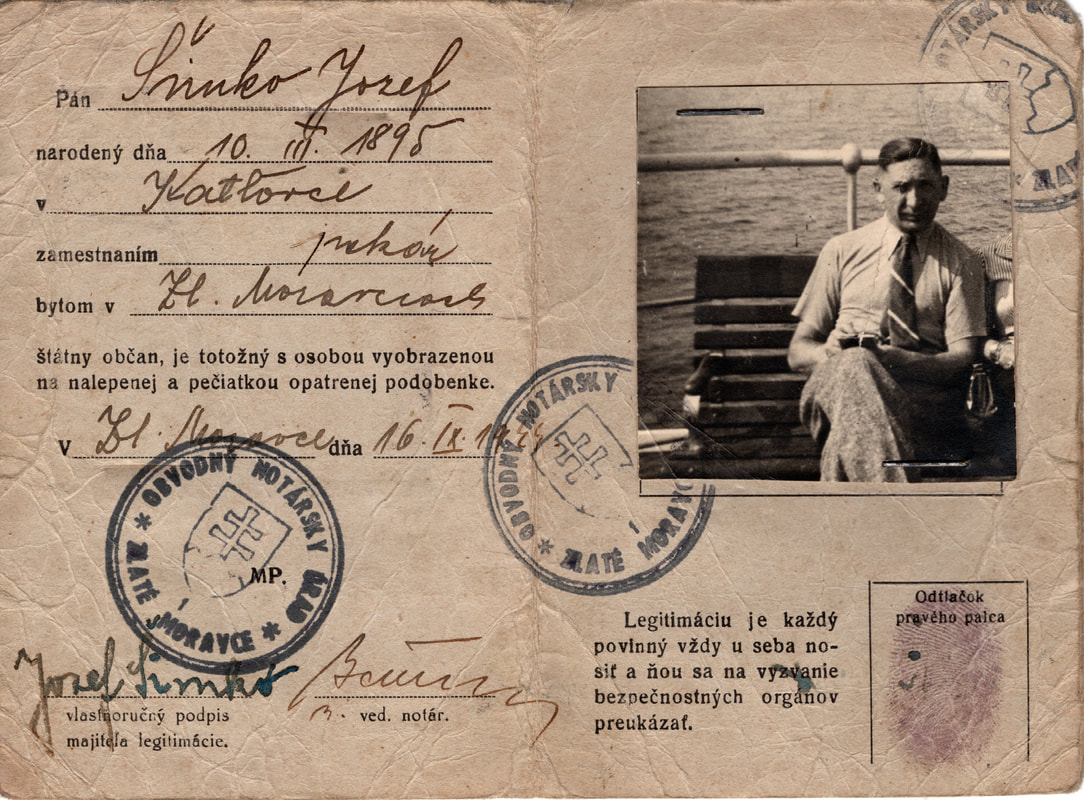

The Reichsfeld ancestors settled in the Austro-Hungarian (Slovak) village of Dehtice, district Trnava, where Herman Reichsfeld was born in 1822. Herman’s son Leopold (Lipota) was born in Dehtice on 14 November 1850. In adulthood, Leopold moved two and one-half kilometers south to Katlovce, a neighboring village where he took a wife Helene (Leni) Hirschmann. The couple soon opened a village inn that became a popular gathering place for food and drink. On 10 April 1895, Berthold, the couple’s sixth and last child and second boy, was born. At age seven-years, Berthold was enrolled in a Slovak school administered by Jesuits in Trnava (22 km south of Dehtice). This was the only school available in the area, even to Jewish families. He later entered gymnázium in Skalica (56 km northwest of Dehtice). Subjects in this school, as in all Slovak schools at the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, particularly after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, were taught in Hungarian.

|

|

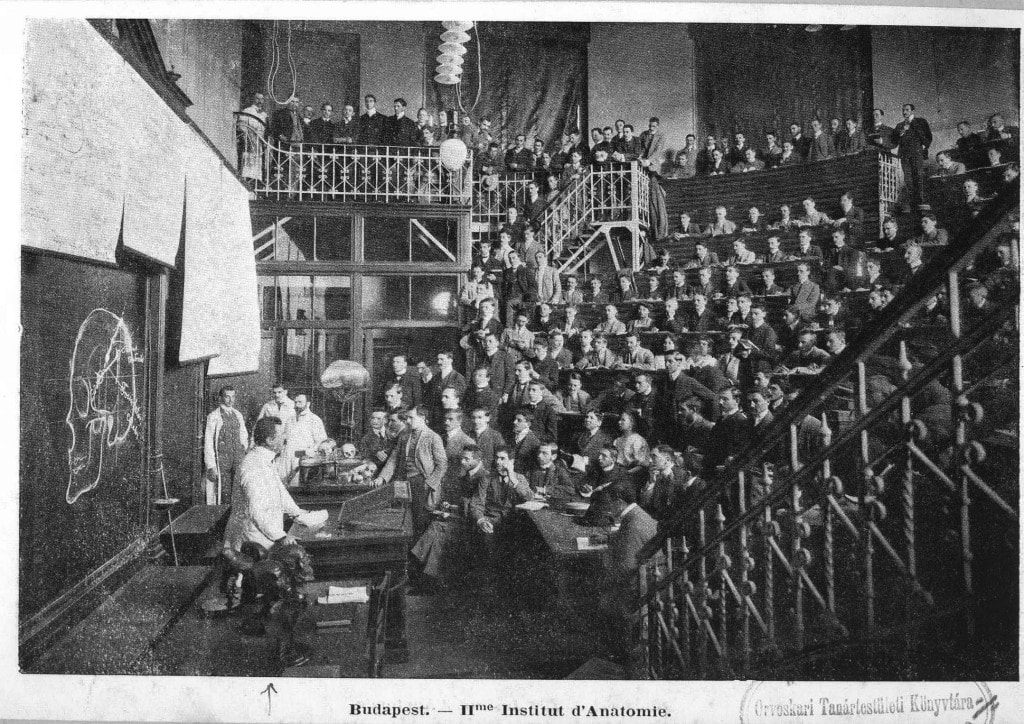

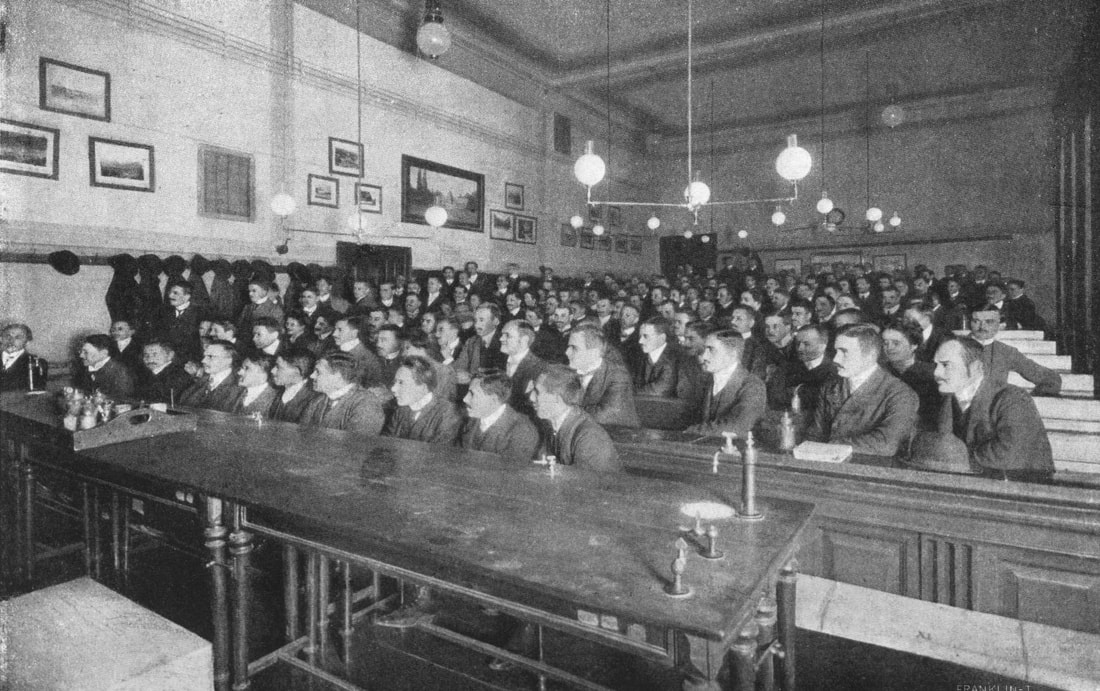

Shortly after graduating from gymnázium in 1913 and with the financial support of his father, Berthold began his medical studies (5-year program) at the Royal Hungarian University of Science in Budapest (Budapesti Királyi Magyar Tudományegyetem).

c. 1910 Budapest, Hungary. Royal Hungarian University of Science in Budapest (known as Semmelweis University since 1969). (Click on above photos to expand to full resolution.)

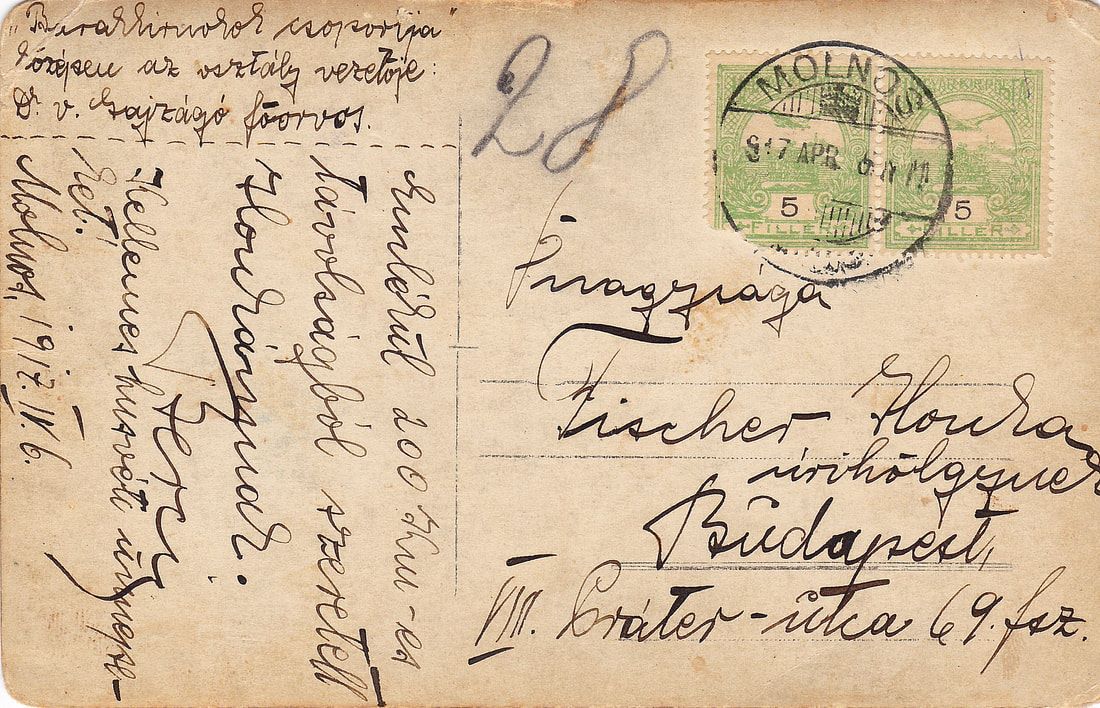

The First World War started when Austria declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914 after the assassination of Austria's Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his German wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg (28 June 1914) in the Bosnian-Serbian town of Sarajevo. The Austro-Hungarian Army immediately began enlisting conscripts and a majority of university professors and students enlisted. As a first-year medical student, Berthold Reichsfeld was among those who enlisted. During his early years in the Army Medical Corps, Berthold was stationed in Italy. Towards the end of the war, he was stationed in Molnos (modern day Mlynárce-Nitra, Slovakia). He managed to complete limited medical studies through the military while serving during the war and successfully passed his military medical certification examination in April 1917. This certification, however, was not equivalent to a full medical diploma awarded by the university, and he could not practice as a physician in civilian life.

The First World War started when Austria declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914 after the assassination of Austria's Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his German wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg (28 June 1914) in the Bosnian-Serbian town of Sarajevo. The Austro-Hungarian Army immediately began enlisting conscripts and a majority of university professors and students enlisted. As a first-year medical student, Berthold Reichsfeld was among those who enlisted. During his early years in the Army Medical Corps, Berthold was stationed in Italy. Towards the end of the war, he was stationed in Molnos (modern day Mlynárce-Nitra, Slovakia). He managed to complete limited medical studies through the military while serving during the war and successfully passed his military medical certification examination in April 1917. This certification, however, was not equivalent to a full medical diploma awarded by the university, and he could not practice as a physician in civilian life.

6 April 1917 Molnos (modern day Mlynárce-Nitra, Slovakia). Photograph of Berthold Reichsfeld (seated at table on left in white coat) undergoing certification testing for military physician by divisional judges headed by the class leader and chief physician Dr. V. Gajzágó.

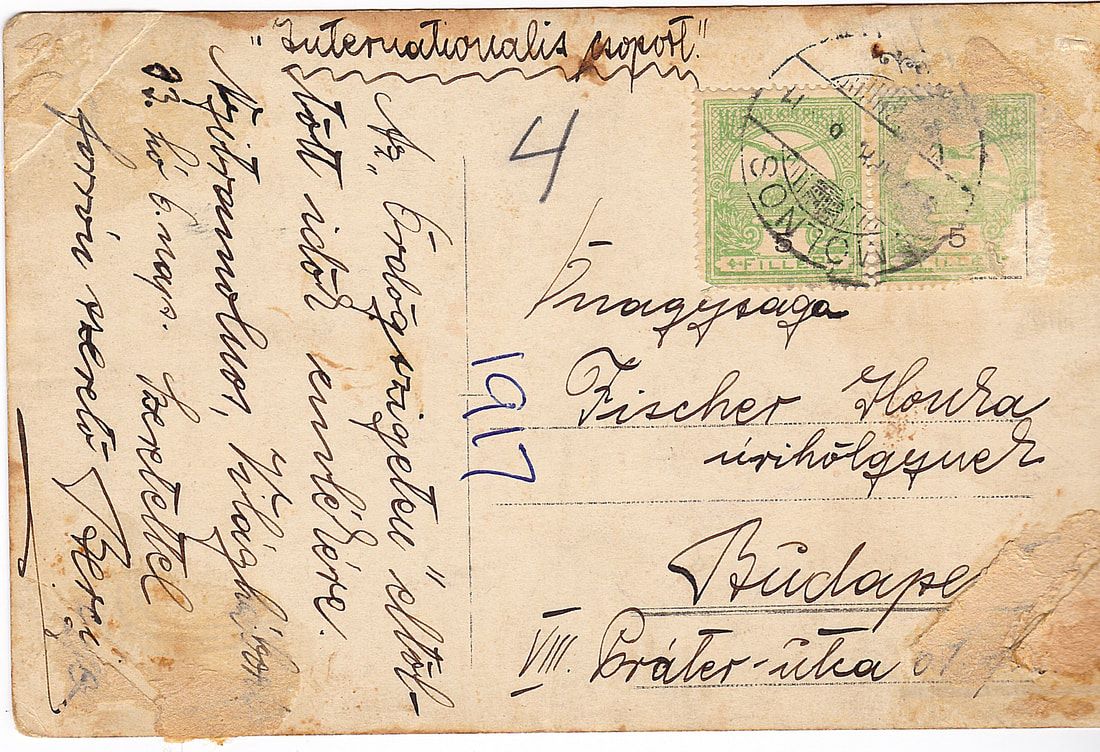

"Your Highness Fischer Ilonka [Helena] exceptional maiden

Budapest VIII Práter Street number 69.

For your remembrance, from 200 km away with love to Ilonka [Helena].

Berci [Berthold]

Pleasant Easter holidays [code for Passover]

Molnos 6 April 1917"

"Your Highness Fischer Ilonka [Helena] exceptional maiden

Budapest VIII Práter Street number 69.

For your remembrance, from 200 km away with love to Ilonka [Helena].

Berci [Berthold]

Pleasant Easter holidays [code for Passover]

Molnos 6 April 1917"

April 1917 Molnos (modern day Mlynárce-Nitra, Slovakia). Photograph of Berthold Reichsfeld seated with his white coat among his military compatriots of the Austro-Hungarian Army during the First World War.

"Your Highness Fischer Ilonka [Helena] exceptional maiden

Budapest VIII Práter Street number 69.

The time spent on the Devil's Island was commemorated by the Nitra-Molnos World War 23 months and 6 days. With love your hot loving Berci."

"Your Highness Fischer Ilonka [Helena] exceptional maiden

Budapest VIII Práter Street number 69.

The time spent on the Devil's Island was commemorated by the Nitra-Molnos World War 23 months and 6 days. With love your hot loving Berci."

c. 1916 Austro-Hungary (Slovakia). This photograph was taken sometime during Berthold Reichsfeld's leave from serving in the First World War as an army physician and before marrying Helena Fischer. The photograph is of the wedding party of Berthold's sister Julia Reichsfeld (back row, far right).

Front row from left: Frida Feldbauer (née Reichsfeld); Leopold (Lipota) Reichsfeld (father of Reichsfelds in this picture); Johanna "Janka" Goráber (née Reichsfeld); David Seidler. Back row from left: Moshe (Moritz) Feldbauer; Berthold Reichsfeld (Georgina's father); Baruch (Bernát) Goráber; Julia Seidler (née Reichsfeld). Missing from the photograph are two older siblings of Berthold, Max Reichsfeld (who immigrated to Argentina as a teenager before the First World War where he married and had three children Helena, Jozef, and one other child) and Mary Reichsfeld (who with her Slovak fiancée Mr. Rakovsky immigrated to New York before the First World War, married, and bore daughters Berta and Paula and sons Leo and Harry). Also missing from the photograph is Leopold Reichsfeld's wife Helene "Leni" (née Hirschmann) who died young after bearing six children. Berthold's older sister Janka was primarily responsible for raising the young Berci after the death of their mother.

Front row from left: Frida Feldbauer (née Reichsfeld); Leopold (Lipota) Reichsfeld (father of Reichsfelds in this picture); Johanna "Janka" Goráber (née Reichsfeld); David Seidler. Back row from left: Moshe (Moritz) Feldbauer; Berthold Reichsfeld (Georgina's father); Baruch (Bernát) Goráber; Julia Seidler (née Reichsfeld). Missing from the photograph are two older siblings of Berthold, Max Reichsfeld (who immigrated to Argentina as a teenager before the First World War where he married and had three children Helena, Jozef, and one other child) and Mary Reichsfeld (who with her Slovak fiancée Mr. Rakovsky immigrated to New York before the First World War, married, and bore daughters Berta and Paula and sons Leo and Harry). Also missing from the photograph is Leopold Reichsfeld's wife Helene "Leni" (née Hirschmann) who died young after bearing six children. Berthold's older sister Janka was primarily responsible for raising the young Berci after the death of their mother.

|

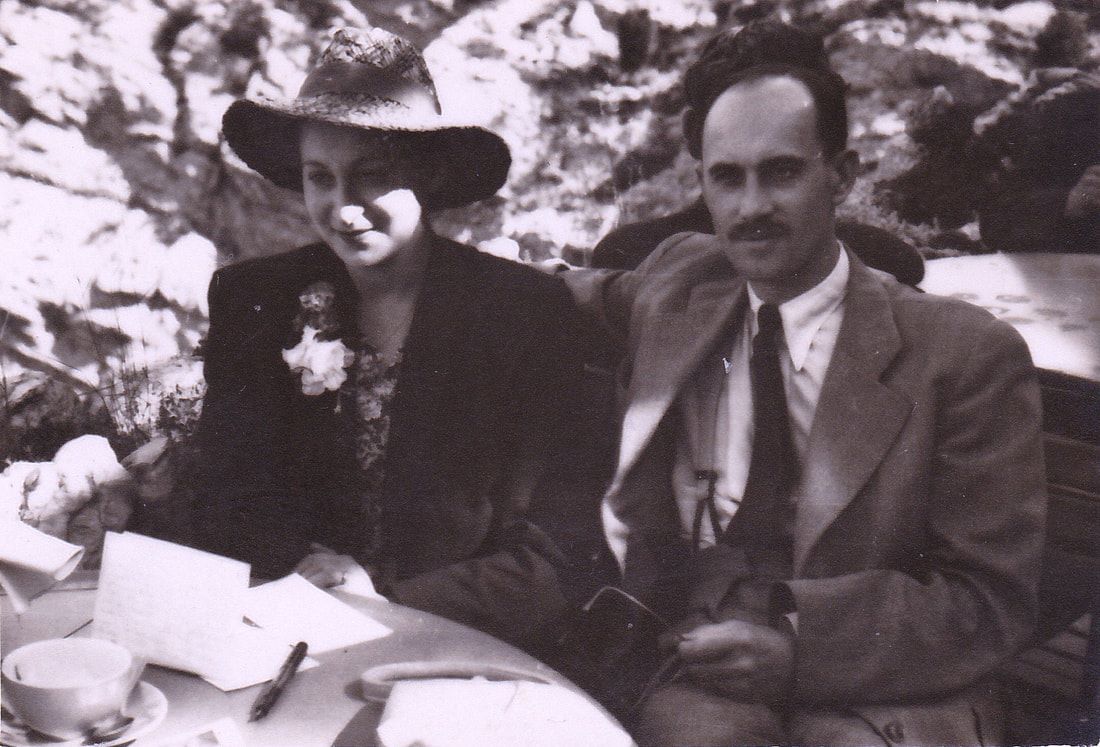

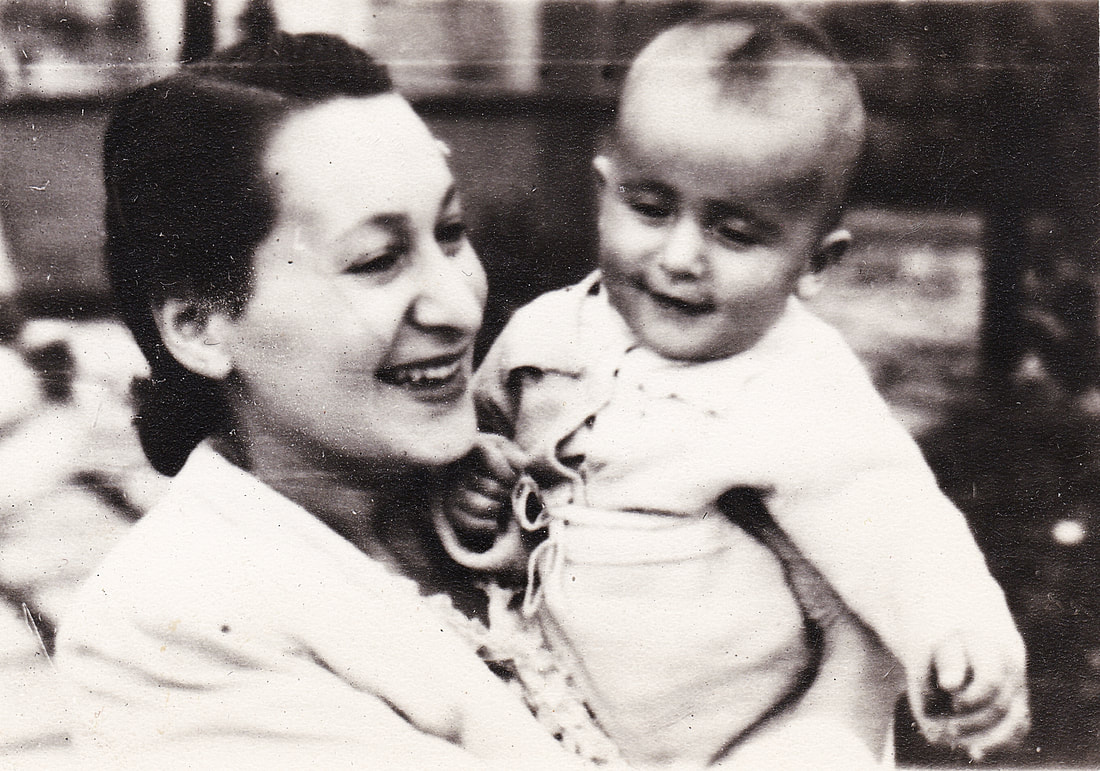

While on leave in Budapest, Berthold met and courted Helena Fischer, the daughter of Jákób and Jozefina Fischer. Born 17 April 1900, Helena was five years Berthold’s junior. Jákób Fischer died from complications of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus when Helena and her older brother Arpád were young children. After the conclusion of World War I, Berthold married 18-year old Helena in Budapest where the two took up residence during the interwar period and tumultuous events in Hungary.

|

Budapest, Hungary

1920 - 1928

1920 - 1928

|

Events in Hungary took a rapid turn for the worse after the devastating loss of the First World War and Treaty of Trianon that cost Hungary two-thirds of its territory and one-third of its native Hungarian speakers. While a prisoner of war in an Imperial Russian prison cell in the Urals, Austro-Hungarian soldier Béla Kun (born Köhn) became interested in Communism and envisioned a Bolshevik Revolution in Hungary. With the collapse of Imperial Russia and withdrawal of Russia from the Entente Powers’ involvement in the First World War, Kun was released from prison by his sworn oath not to rejoin the Central Powers. In March 1918, in Moscow, Kun co-founded the Hungarian Group of the Russian Communist Party (the predecessor to the Hungarian Communist Party). He travelled widely, including to Petrograd and Moscow where he befriended Vladimír Lenin. In the Russian Civil War in 1918, Kun fought for the Bolsheviks. During this time, he initiated concrete plans for a communist revolution in Hungary. In November 1918, with at least several hundred other Hungarian

|

communists and with a large sum of money provided by the Soviets, he returned to Hungary and managed to establish the Hungarian Soviet Republic (the first communist government in Europe outside of Russia) ousting Hungary’s first democratic government on 21 March 1919.

|

The first action of the new Hungarian Soviet Republic was the nationalization of most of the private property in Hungary. Despite advice from Lenin and the Bolsheviks, Béla Kun’s government chose not to redistribute land to the peasantry, which fragmented their support in Hungary. Instead, all land was to be converted into collective farms and former estate owners, managers, and bailiffs were to be retained as the new collective farm managers. This resulted in the dissolution of the balance of power between the old elite and the peasantry which made up the majority of Kun’s support. In an effort to win peasant support, Kun cancelled all taxes in rural areas. To provide food for the cities, the Soviet Republic requisitioned food in the countryside through a red militia known as the Lenin Boys.

|

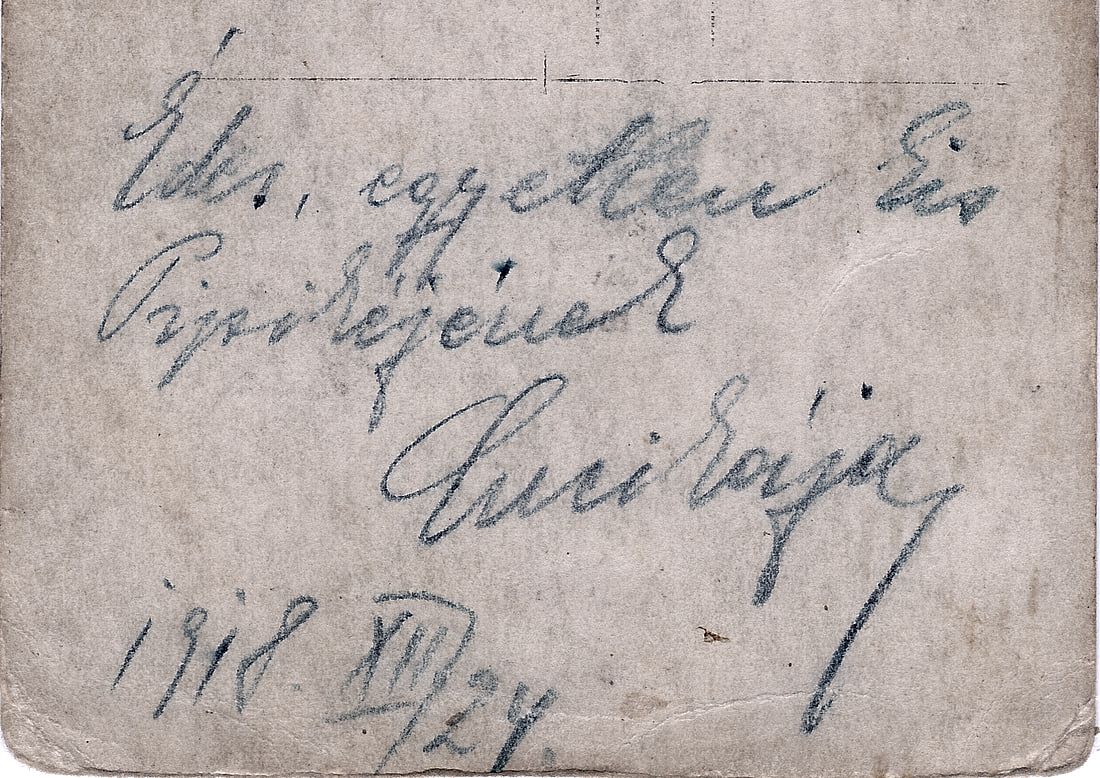

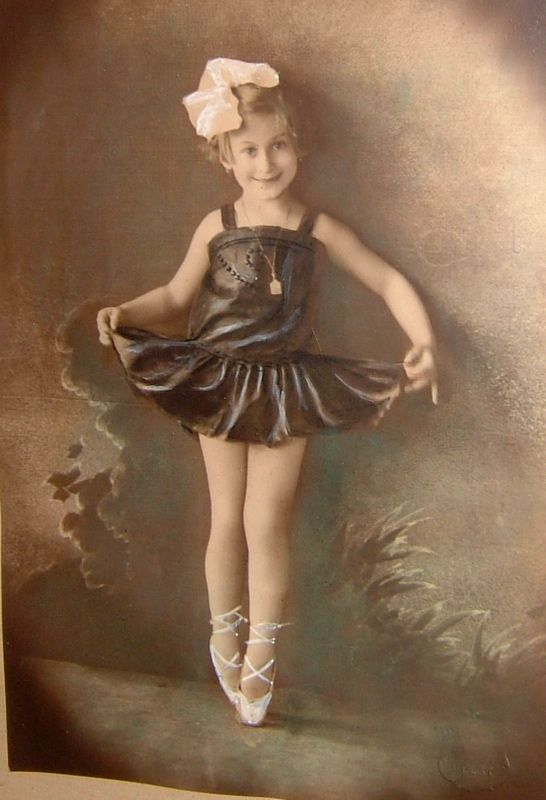

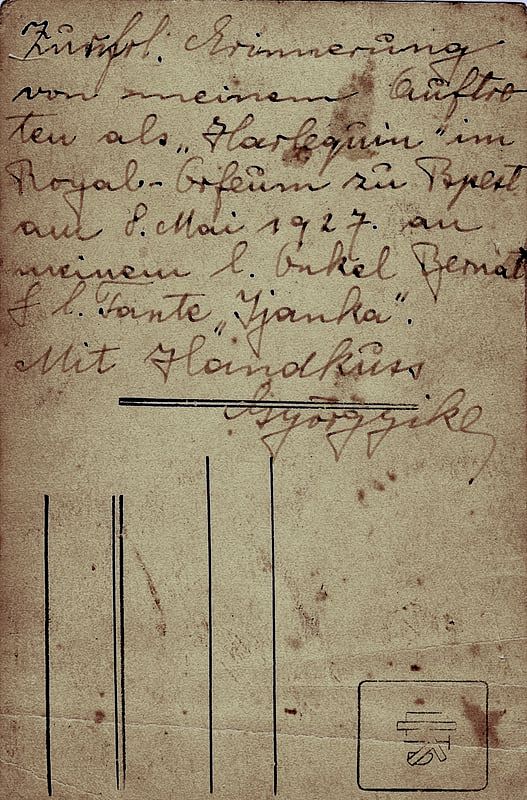

c. 1925 Budapest, Hungary. Georgina in ballet school.

|

This caused additional conflict between Kun and his supporters in the countryside. On 24 June, an attempt to overthrow the communist regime failed. A brutal retaliation for the coup attempt was exacted by the secret police, revolutionary tribunals, and semiregular detachments—such as Commissar for Military Affairs Tibor Szamuely’s bodyguards, known as the Lenin Boys and commanded by József Cserny—and became known as the Red Terror. Of those arrested, an estimated 600 were killed, mostly anti-communist intellectuals. Former Social Democrats such as József Pogány, relatively moderate supporters of Kun, played a major limiting factor on the reprisals, which would have otherwise been far more extensive.

The short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic precipitated the formation of the intensely anti-communist movement under Vice Admiral Miklós Horthy de Nagybanya (1868-1957) and his National Army (Nemzeti Hadsereg). Admiral Horthy led the counterrevolutionaries and their government from the southern city of Szeged and entered Budapest. In retaliation for Kun’s Red Terror, responsible for up to 600 deaths, reactionary military units of the counterrevolutionary government exacted revenge in a two-year wave of violent repression later known as the White Terror. These reprisals were organized and carried out by right-wing officer detachments of Horthy’s National Army. |

|

The aims of the reactionary officers’ junta were revealed by reports published in Vienna newspapers concerning a meeting held in the War Office in Budapest. During this meeting, a resolution was presented that called for the establishment of a military dictatorship, and recommended, as preliminary measures, the seizure of the railroad terminals, post and telegraph offices and telephone exchanges, disarmament of the police, confiscation of all property owned by Jews, destruction of the plants of liberal and Jew-owned newspapers, and the general massacre of all radicals, socialists, and Jews. The victims of the White Terror were primarily communists, social democrats, and Jews. Most Hungarian Jews were not supporters of the Bolsheviks, but a majority of the leadership of the Hungari- |

an Soviet Republic was comprised of young Jewish intellectuals, and anger over the communist revolution easily translated into anti-Semitic hostility. In 1920 and 1921, internal chaos afflicted Hungary. The White Terror continued to plague Jews and leftists, unemployment and inflation soared, and penniless Hungarian refugees poured across the border from neighboring countries burdening the floundering Hungarian economy. The government offered the population little succor. In January 1920, Hungarian men and women cast the first secret ballots in the country’s political history and elected a large counterrevolutionary and agrarian majority to a unicameral parliament. Two main political parties emerged: the social conservative Christian National Union and the Independent Smallholders’ Party, which advocated land reform. On 1 March 1920, the parliament annulled both the Pragmatic Sanction of 1723 and the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, and it restored the Hungarian monarchy but postponed choosing a king until civil disorder had subsided. Meanwhile the same day, the Hungarian Parliament elected Miklós Horthy regent and empowered him, among other things, to appoint Hungary’s prime minister, veto legislation, convene or dissolve the parliament, and command the armed forces.

(Continued below under "Budapest to Bratislava.")

(Continued below under "Budapest to Bratislava.")

|

Budapest was not always the vibrant Central European city that it is sometimes shown to have been, at least not under that name. It was essentially three separate municipalities within the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the districts of Buda, Pest, and Obuda were combined in 1873. This, together with the earlier Compromise Agreement of 1867, which set up the joint monarchy, and the Emancipation Decree of the same year, which “granted Jews full political and civic equality in the Hapsburg lands,” led to the rapid development of Budapest as a rival to Vienna. Showcasing the city was meant to send a signal to the world that Hungary was a major power in the region. And the high percentage of Jews in Budapest (Mary Gluck gives a figure of 23% by 1900) indicated that they played a prominent part in the life of the city. In the decades between 1880 and 1914, Budapest became famous for its edgy music halls, opulent Orpheums, and titillating all-night coffee houses, which were widely admired and emulated throughout Central Europe.

|

|

The Budapest Royal Orpheum—a decadent cabaret that hosted the best acts of its time, including the American dancer and French vedette singer Josephine Baker, one of the most celebrated performers at the Folies Bergère in Paris and an icon of the jazz age—was infamous among European varieté theatres. The Royal Orpheum, built by Hermann Keleti and Oszkár Fodor, opened its doors on 3 October 1908. The European Orpheum circuit enjoyed its golden age between 1880 and 1914, and pioneered one of the most important and innovative entertainment industries of its age. Widely emulated in Vienna and Berlin, the Budapest Orpheum helped transform the Hungarian capital into the popular entertainment center of German-speaking Central Europe. Less widely known is the close identification between the Orpheum and the city’s lower middle-class Jewish population, which supplied the owners, directors, writers, actors, and most of the audiences of these popular musical reviews.

|

22 August 1927 Piešťany Spa, Czechoslovakia (modern day Slovakia). Leopold Reichsfeld seated wearing hat second from right on third bench from front.

|

Budapest to Bratislava (continued from above)

Hungary’s forced signing of the Treaty of Trianon on 4 June 1920, ratified the country’s dismemberment, limited the size of its armed forces, and required reparations payments. The territorial provisions of the treaty, which ensured continued discord between Hungary and its neighbors, required the Hungarians to surrender more than two-thirds of their prewar lands. The new international borders separated Hungary’s industrial base from its sources of raw materials and its former markets for agricultural and industrial products. These new circumstances forced Hungary to become a trading nation. Hungary lost 84 percent of its timber resources, 43 percent of its arable land, and 83 percent of its iron ore. Because most of the country’s prewar industry was concentrated near Budapest, Hungary retained about 51 percent of its industrial population, 56 percent of its industry, 82 percent of its heavy industry, and 70 percent of its banks. Horthy appointed reactionary Transylvanian nobleman and former Minister of Foreign Affairs Count Pál Teleki as Prime Minister in July 1920. Teleki’s right-wing government nearly immediately passed the Numerus Clausus Act. The law formally placed limits on the number of minority students at universities, legalized corporal punishment, and, to quiet rural discontent, took initial steps toward fulfilling a promise of major land reform by dividing about 385,000 hectares from the largest estates into small holdings. Though the text of the law did not use the term Jew, it |

was nearly the only group overrepresented in higher education. The policy is often seen as the first Anti-Jewish Act of twentieth century Europe. Its aim was to restrict the number of Jews in higher education to 6 percent, which was their proportion in Hungary at that time. Before the First World War, the percentage of Jews among university students was around 25%, and by 1918 reached 36%.

Bratislava, Czechoslovakia

1928 - 1938

1928 - 1938

|

Under Prime Minister Teleki, the White Terror continued unabated. Ultimately, tens of thousands were imprisoned, up to 5,000 were murdered, and nearly 100,000 people were forced to leave the country, most of them socialists, intellectuals, and middle-class Jews.

In March and October 1921, Horthy thwarted two attempts by former Austrian Emperor Charles I (1887-1922) to regain the Hungarian throne. Teleki’s government resigned after the failed attempts by Charles I. King Charles’ attempted return split parties between conservatives who favored a Habsburg restoration and nationalist right-wing radicals who supported coronation of a Hungarian king. István Bethlen, a nonaffiliated right-wing member of the parliament, took advantage of this rift by convincing members of the Christian National Union who opposed Charles’ re-enthronement to merge with the Smallholders’ Party and form a new Party of Unity with Bethlen as its leader. Horthy then appointed Bethlen Prime Minister. As Prime Minister, Bethlen dominated Hungarian politics between 1921 and 1931. He fashioned a political machine by amending the electoral law, eliminating peasants from the Party of Unity, providing jobs in the bureaucracy to his supporters, and manipulating elections in rural areas. Bethlen restored order to the country by giving the radical counterrevolutionaries payoffs and government jobs in exchange for ceasing their campaign of terror against Jews and leftists. |

|

In 1921, Bethlen made a deal with the Social Democrats and trade unions, agreeing, among other things, to legalize their activities and free political prisoners in return for their pledge to refrain from spreading anti-Hungarian propaganda, calling political strikes, and organizing the peasantry. In May 1922, the Party of Unity captured a large parliamentary majority.

When Bethlen took office, the government was all but bankrupt. Tax revenues were so paltry that he turned to domestic gold and foreign-currency reserves to meet about half of the 1921-22 budget and almost 80 percent of the 1922-23 budget. Further compounding Hungary’s problems was the fact that of its four neighbors, three (Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia) were enemies and kept troops stationed on their borders at all times, even though Hungary had an army of only 20,000 men. The fourth, Austria, was a struggling nation and little more than an economic competitor. By the late 1920s, Bethlen’s policies had brought order to the economy. However, the apparent stability was supported by a rickety framework of constantly revolving foreign credits and high world grain prices; therefore, Hungary remained undeveloped in comparison with the wealthier western European countries, as most of the foreign loans went for non-productive purposes such as graft, expanding bureaucracy, and monumental public works projects. |

|

Despite economic progress, the workers’ standard of living remained poor, and consequently the working class never gave Bethlen its political support. The labor movement had never developed in pre-World War I Hungary the way it did in Austria, and the Horthy government remained resolutely opposed to organized labor or social reforms. There was no minimum wage or any sort of labor laws in Hungary almost until the start of World War II, and wages were further undercut by peasants flocking into Budapest who were willing to work for almost nothing. On the whole, workers fared more poorly in interwar Hungary then they had before World War I. The peasants were even worse off than the working class. In the 1920s, about 60 percent of the peas- |

|

ants were either landless or were cultivating plots too small to provide a decent living. Real wages for agricultural workers remained below prewar levels, and the peasants had practically no political voice. Moreover, once Bethlen had consolidated his power, he ignored calls for land reform. The industrial sector failed to expand fast enough to provide jobs for all the peasants and university graduates seeking work. Most peasants lingered in the villages, and in the 1930s Hungarians in rural areas were extremely dissatisfied. Hungary’s foreign debt ballooned as Bethlen expanded the bureaucracy to absorb the university graduates who, if left idle, might have threatened civil order. This was because Hungary, like the rest of Eastern Europe, had an educational system primarily focused on the liberal arts and law rather than science, engineering, or other practical subjects that might have helped the country’s development.

At the end of the First Word War, anti-Semitism became an element in the competition between the various Hungarian elites. Prior to the First World War, social roles in Hungary had been very distinct: the Christian middle classes had sent their sons to work for the state or for local government offices, while the Jewish middle classes had sent their sons to work in non-state-controlled sectors. Among market-controlled professions, the ratio of middle-class Jews was very high. Nationally, Jews |

|

comprised 42% of all journalists, and in Budapest the ratio was 48%. Jews also accounted for 53% of Hungary’s commercial executives, and 64% in Budapest. Moreover 45% of lawyers and 43% of legal staff were Jewish. On the other hand, the Christian middle classes were over-represented amongst public officials. After the 1920 Treaty of Trianon, which greatly reduced Hungary’s territory, the country needed far fewer public officials. This meant that the Christian middle classes were obliged to secure positions outside the state-controlled areas. When they could not obtain work in the commercial market, either because they lacked useful skills or because the commercial market was saturated with Jews, the Christian middle classes would invariably blame their bad luck on Jews. The Treaty of Trianon was followed by the mass migration into Hungary of middle-class Hungarian-speakers from the successor states, resulting in stiff competition for positions and jobs. Against this background of increased competition, the Christian middle classes turned to the executive power for assistance in their struggle against the Jews. Nevertheless, the increased level of competition was not enough to persuade the Hungarian middle classes—so proud of their Corpus Iuris, the symbol of their adherence to Europe—to transform the Hungarian legislative into a means of violently suppressing the Jews. Right- |

wing public opinion began to argue that liberalism, radicalism, and social democracy—all of which it perceived as manifestations of “Jewish cosmopolitism”—were responsible for the collapse of the historical kingdom of Hungary. “National sentiment,” which had been a natural associate of liberalism in the nineteenth century, became locked in a conflict with “liberal sentiment.” In the end, the middle classes chose nationalism rather than liberalism, discarding the old principles of equality and human rights and giving the green light to restrictions against Jews. Although it was evidently the extreme right wing rather than the political center that gave the concrete impetus to the adoption of the Numerus Clausus Act of 1920 (Law No. XXV), nevertheless without this “state of competition” and the “contradiction between nationalism and liberalism,” the country’s elite might never have been willing to tolerate anti-Semitism in the form of a parliamentary act. These developments would contribute to a growing anti-Semitism in Hungary that would ultimately have tragic consequences in the 1940s.

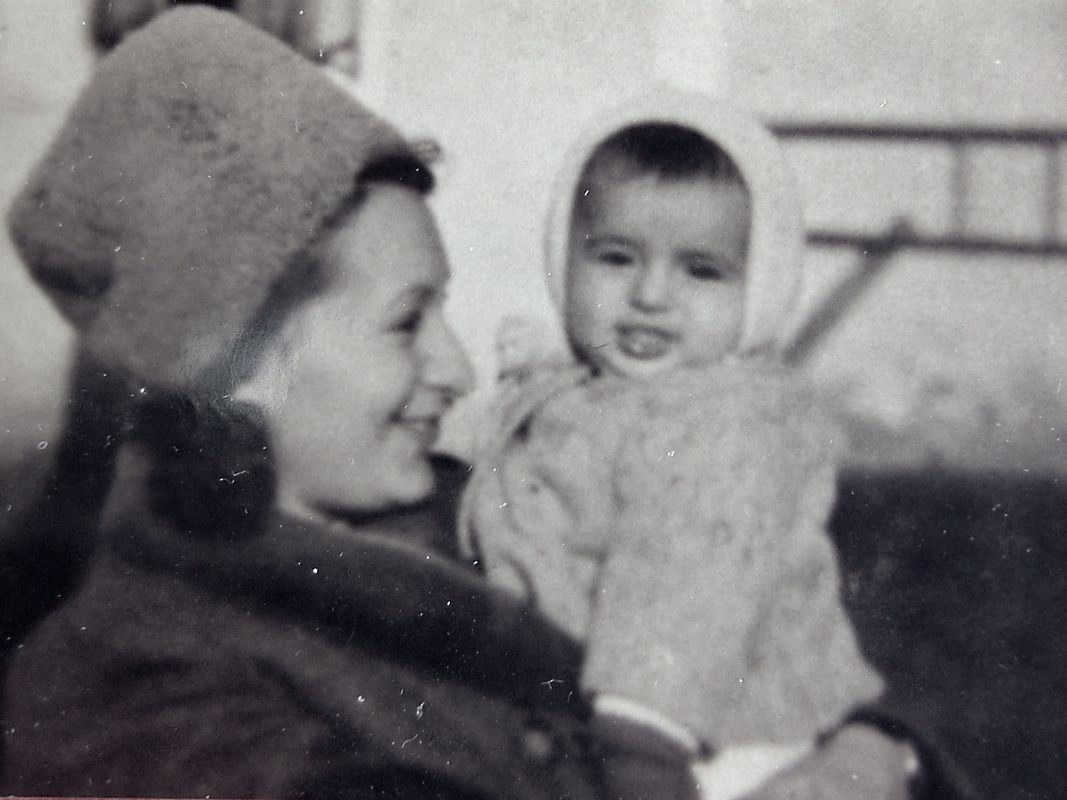

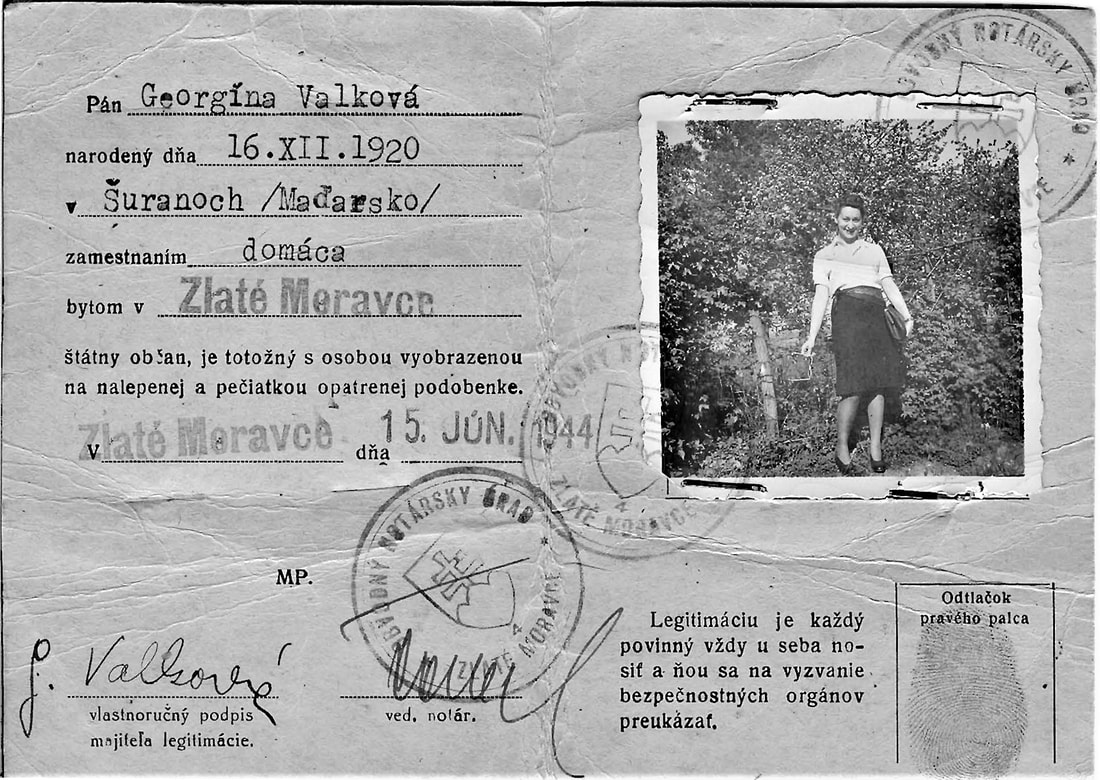

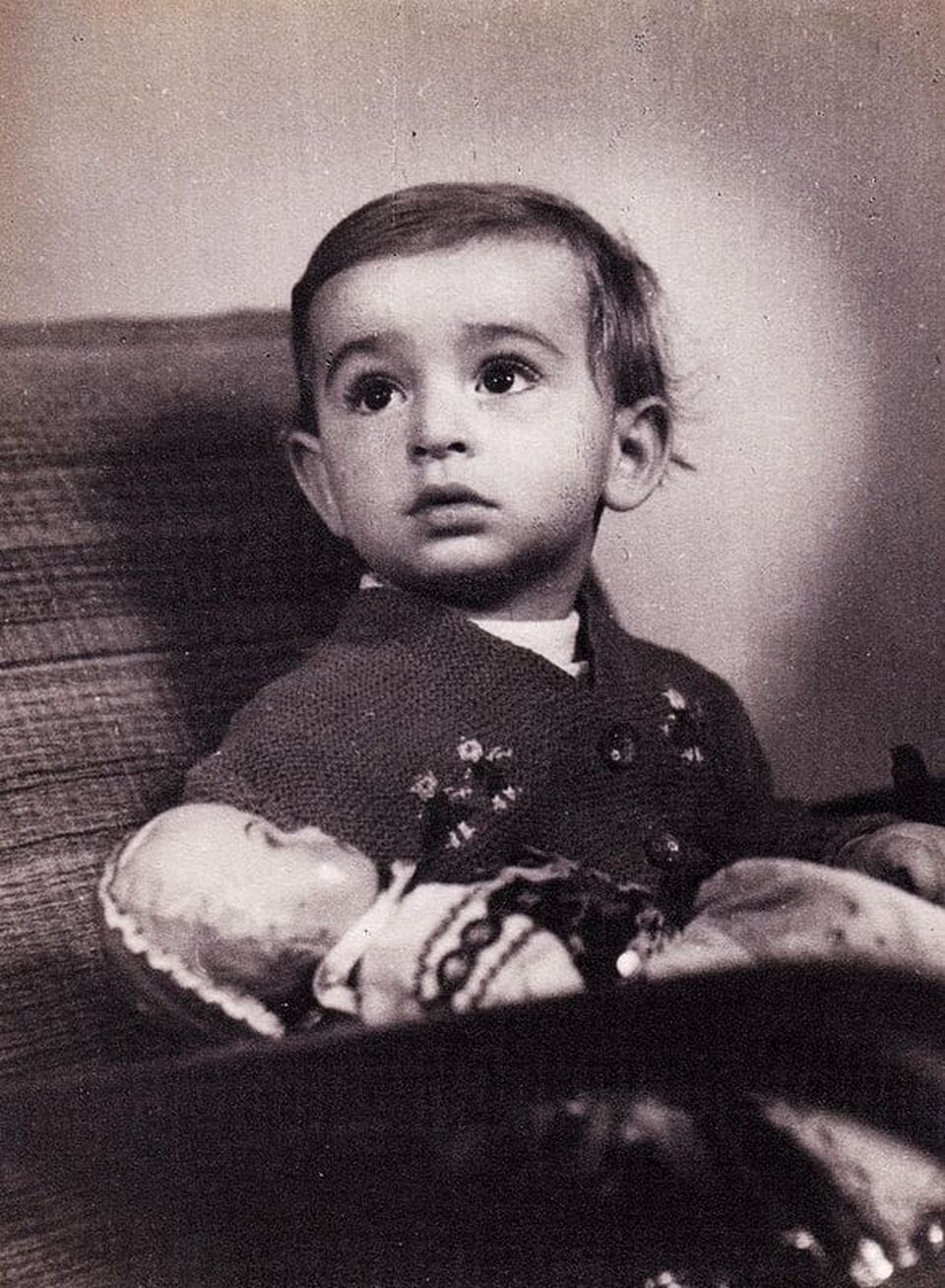

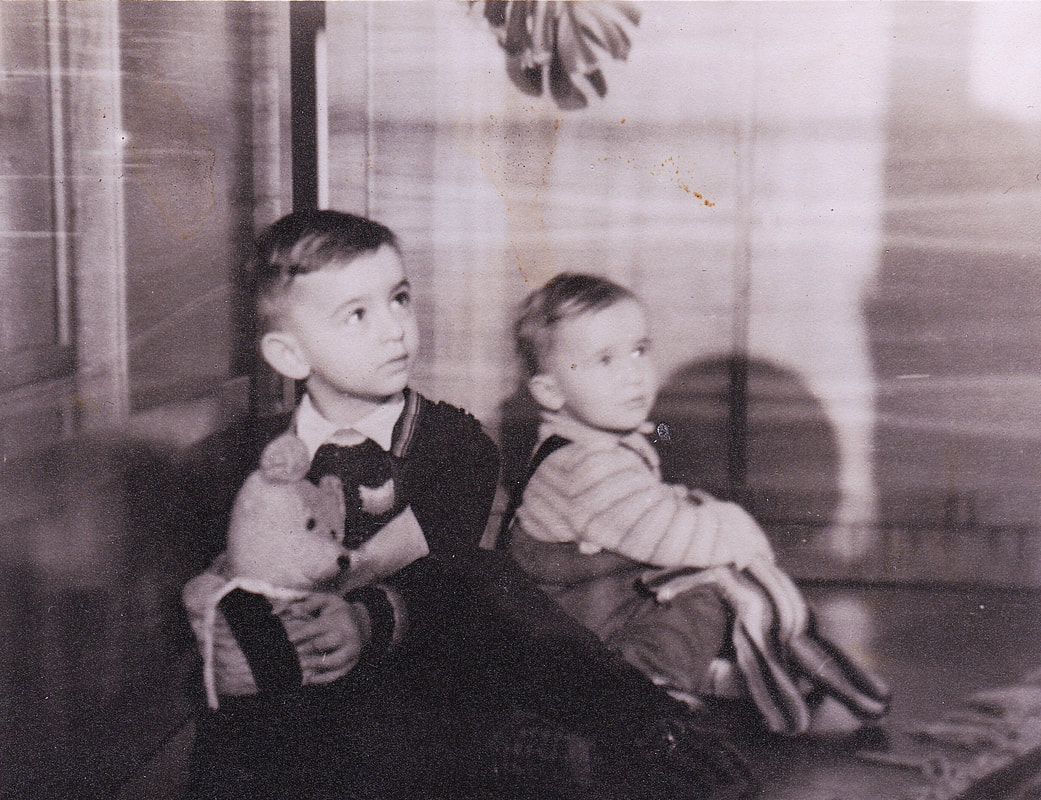

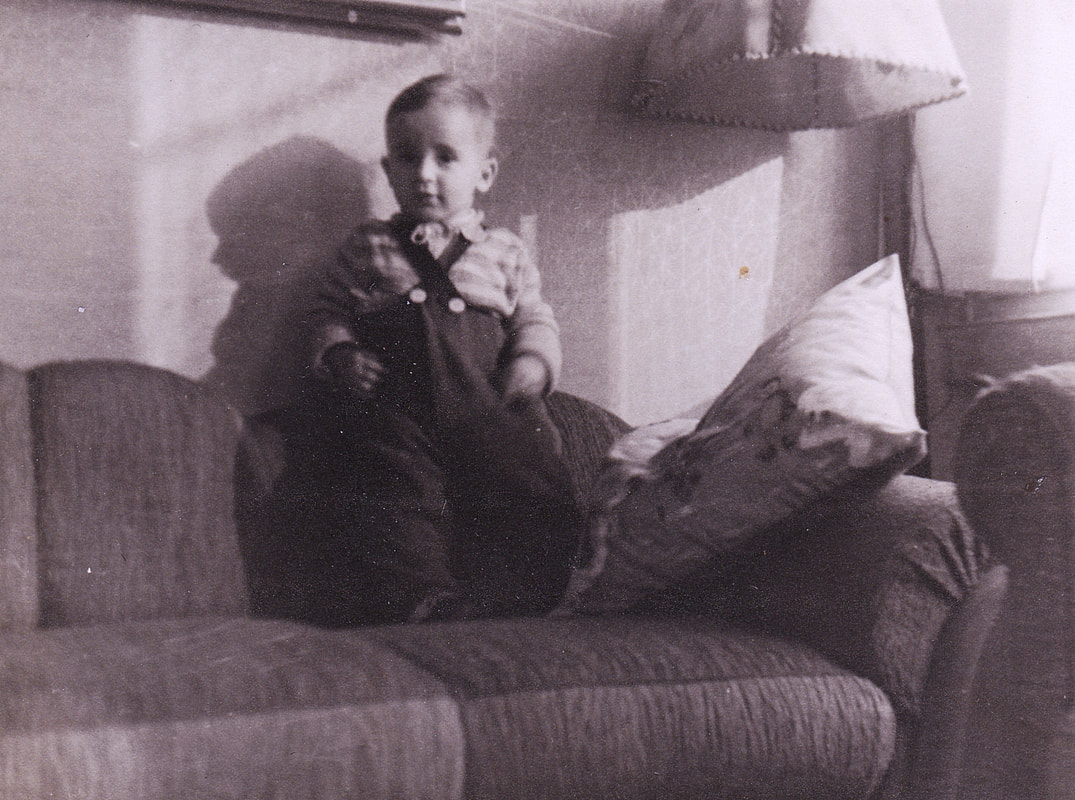

The worsening conditions in Hungary clearly influenced the stability of the Reichsfeld household in Budapest and was the final chapter in Berthold’s hopes of returning to the university and finishing his medical degree. Instead of a doctorate in medicine, Berthold Reichsfeld was blessed and burdened with a child on 16 December 1920—Györgyi (pronounced “Dyurdy”; known as Jirka in Slavic languages and Georgina in English). Only his former officer’s position and service in the Austro-Hungarian Army during the First World War provided a modicum of protection during the Red and White Terror. However, during the rule of the Teleki government he faced increasing pressure to denounce his Czechoslovak citizenship and adopt Hungarian citizenship. He refused and rebuffed this pressure. Consequently, he was unemployed for the most part.

The worsening conditions in Hungary clearly influenced the stability of the Reichsfeld household in Budapest and was the final chapter in Berthold’s hopes of returning to the university and finishing his medical degree. Instead of a doctorate in medicine, Berthold Reichsfeld was blessed and burdened with a child on 16 December 1920—Györgyi (pronounced “Dyurdy”; known as Jirka in Slavic languages and Georgina in English). Only his former officer’s position and service in the Austro-Hungarian Army during the First World War provided a modicum of protection during the Red and White Terror. However, during the rule of the Teleki government he faced increasing pressure to denounce his Czechoslovak citizenship and adopt Hungarian citizenship. He refused and rebuffed this pressure. Consequently, he was unemployed for the most part.

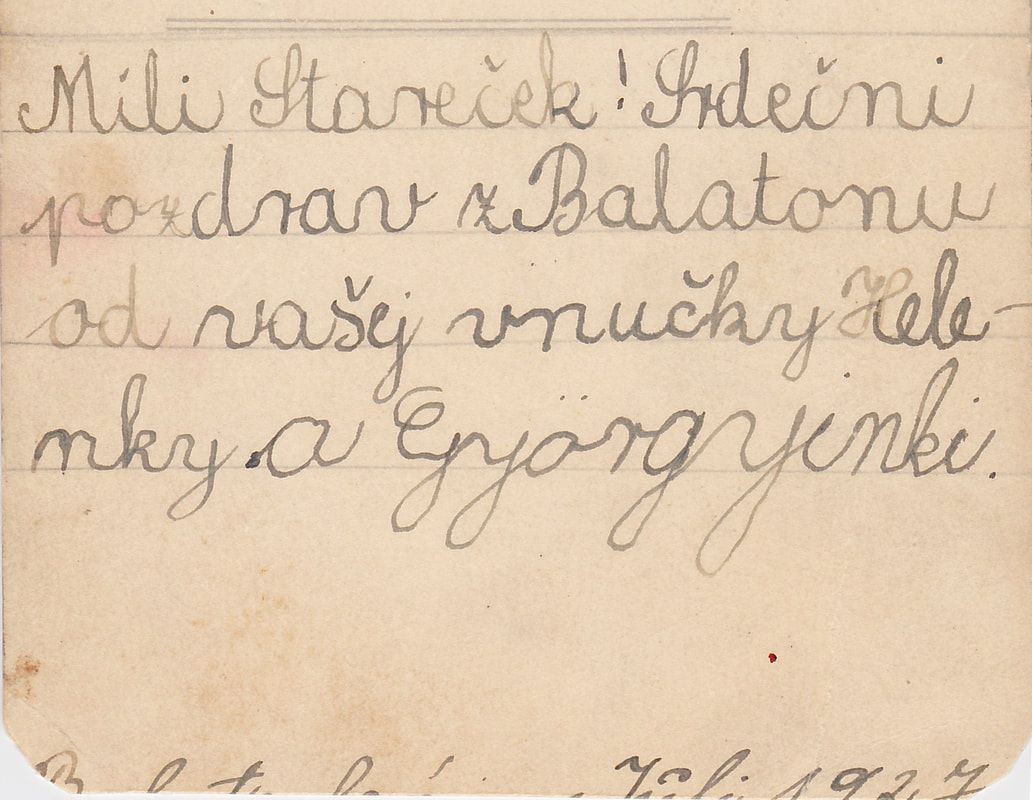

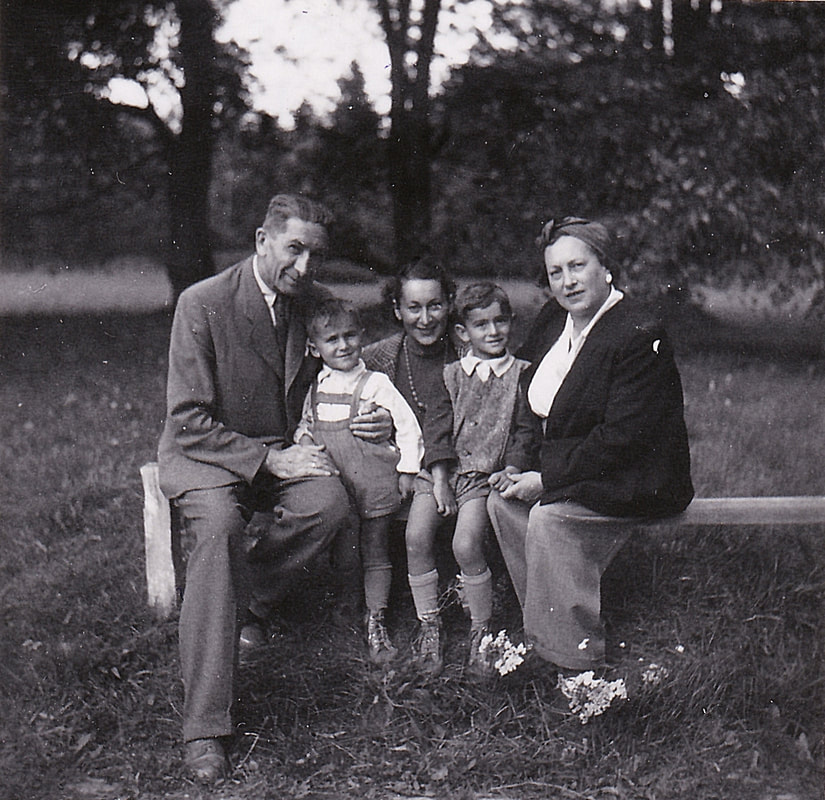

In 1928, one year before the Great Depression, the Reichsfelds concluded they needed to leave Hungary and move to the more stable and Democratic Czechoslovakia—the homeland of Berthold’s modern ancestors—where they could settle in Bratislava. However, before moving to Bratislava permanently, they temporarily lived with Berthold’s older sister Johanna and her family, the Gorábers, in the village of Hradište pod Vrátnom (100 km northeast of Bratislava and 16 km southeast of Senica where Berthold’s sister Frida lived with her husband Moritz Feldbauer). Berthold’s widowed father Leopold was also living with the Gorábers at the time. In Hradište pod Vrátnom, Georgina enrolled in the village primary school exchanging her native Hungarian for Slovak. The Reichsfelds remained in Hradište pod Vrátnom until the end of the scholastic year in 1929 when they moved to Bratislava. The ambitions of her parents demanded that their daughter receive a better education than they felt the Slovak schools could offer. And so, before Georgina could learn to speak fluently the language of her adopted country, she was sent to a summer language camp near Vienna to acquire a working knowledge of German, which had replaced Hungarian as the predominant language of college preparatory education.

Once settled in Bratislava, Berthold’s employment opportunities improved. He trained for and took a position as an insurance agent with the Bratislava branch of the Italian insurance company Riunione Adriatica di Sicurtà. Living in Bratislava also presented Berthold the opportunity to explore resuming his medical studies. He enrolled in anatomy and cadaver dissection courses with the Faculty of Medicine at Comenius University (Lekárska fakulta Univerzity Komenského) located at Sasinkova Street No. 2. Initially established by the new parliament in Prague as the Czecho-Slovak State University in Bratislava on 27 June 1919, it was renamed in November 1919 after the Moravian world-renowned “father of modern education” Jan Amos Komenský (1592-1670, Latin: Iohannes Amos Comenius). The Faculty of Medicine, established on 21 September 1919, was the first faculty at the Czecho-Slovak State University in Bratislava. Only 10 years after its establishment, Berthold Reichsfeld hoped for a second chance to achieve his dream of becoming a physician. As a preteen, Georgina would sometimes accompany her father to his cadaver dissection sessions. Unfortunately for the Reichsfelds, economic and political constraints forced Berthold to permanently relinquish his dream of becoming a physician. He simply could not manage paying for his medical studies while supporting his family.

Georgina participated in Sokol in Bratislava. Sokol was a cultural and gymnastics organization first founded in Prague in the Czech region of Austria-Hungary in 1862 by Miroslav Tyrš and Jindřich Fügner. It was based upon the principle of “a strong mind in a sound body.” Through lectures, discussions, and group outings, Sokol provided what Tyrš viewed as physical, moral, and intellectual training for the nation. This training extended to men of all ages and classes, and eventually to women. All four of Georgina's children participated in Sokol in the United States.

|

Neologs (Hungarian: neológ irányzat, “Neolog Faction”) are one of the two large communal organizations among Hungarian Jewry. Socially, the liberal and modernist Neologs had been more inclined toward integration into Hungarian society since the Era of Emancipation in the 19th century. This was their main feature, and they were largely the representative body of urban, assimilated middle- and upper-class Jews. Religiously, the Neolog rabbinate was influenced primarily by Zecharias Frankel’s Positive-Historical School, from which Conservative Judaism evolved as well, although the formal rabbinical leadership had little sway over the largely assimilationist communal establishment and congregants. Their rift with the traditionalist

|

and conservative Orthodox Jews was institutionalized following the 1868–1869 Hungarian Jewish Congress that resulted in schism in Hungarian Jewry, and they became a de facto separate denomination. When faced with the need to choose between the two, a third faction of “Status Quo” congregations emerged, refusing to join either and remaining fully autonomous, without a higher authority. While a large proportion of communities retained a cohesive affiliation to one group, some communities were affected by the schism, and formed two or even three new congregations, with separate affiliations. The threefold pattern remained a key feature of Hungarian Jewry for generations, even in the territories ceded under the 1920 Treaty of Trianon (including Slovakia), until its destruction during the Holocaust.

The Reichsfelds attended the Neolog synagogue in Old Town Bratislava. The synagogue of the Neolog Jewish community stood in the Podhradie zone of the Jewish Quarter until 1969, when it was demolished to make way for construction of the SNP Bridge. The two-story Moorish building with two octagonal onion-domed towers was built in 1893 based on the designs of Dezső Milch. The Neolog community in Bratislava was established in 1871 by a secessionist group unhappy with the strong Orthodox leadership of the Jewish community. The synagogue was constructed on a square adjacent to St. Martin’s Cathedral, and was a major landmark often depicted on postcards. The building served as a television studio during the post-war period. It was here that Eugen Bárkány oversaw his Judaica collection of the Bratislava Jewish community, which he planned to establish as the “Slovak Jewish Anti-Fascist Museum” in the synagogue. The Decalogue from the synagogue façade is preserved in the Jewish Community Museum in Bratislava.

The Reichsfelds attended the Neolog synagogue in Old Town Bratislava. The synagogue of the Neolog Jewish community stood in the Podhradie zone of the Jewish Quarter until 1969, when it was demolished to make way for construction of the SNP Bridge. The two-story Moorish building with two octagonal onion-domed towers was built in 1893 based on the designs of Dezső Milch. The Neolog community in Bratislava was established in 1871 by a secessionist group unhappy with the strong Orthodox leadership of the Jewish community. The synagogue was constructed on a square adjacent to St. Martin’s Cathedral, and was a major landmark often depicted on postcards. The building served as a television studio during the post-war period. It was here that Eugen Bárkány oversaw his Judaica collection of the Bratislava Jewish community, which he planned to establish as the “Slovak Jewish Anti-Fascist Museum” in the synagogue. The Decalogue from the synagogue façade is preserved in the Jewish Community Museum in Bratislava.

|

In Bratislava, Georgina continued her elementary education in a German school. Two years at the German elementary school enabled her at the age of ten-years (autumn 1931) to test for and be accepted to the 1931–1932 academic year at Deutsches Staatsrealgymnasium (now known as Deutsche Schule Bratislava) at the intersection of Palasády and Kuzmányho streets—a 15-minute walk from her parents’ apartment on Hviezdoslavovo námestie[1] near the Danube River. Because of Bratislava’s close geographical and historical proximity to Austria and Hungary, the citizenry spoke three languages, Slovak (Bratislavans spoke a mix of Czech and Slovak at the time), Hungarian, and German. The Jewish population,[2] which controlled most of the city’s business, favored a knowledge of all three languages. By 1939, the year Georgina graduated from gymnázium, she had mastered German, French, and Latin, and had working knowledge of Czechoslovak and Hungarian. (See footnotes, below.)

|

With the aid of her parents, Georgina managed to timely graduate from gymnázium in 1939. In the years following her graduation, Georgina had no chance of employment or further education. The growing violence against Jews in public prevented Georgina from venturing out very often. Over the course of the ensuing nearly two years after her graduation, Georgina limited her activities away from her home by joining a swim club at the Grössling pool on Grösslingová street in Bratislava and getting together with her Jewish friends on occasion at each other’s homes where they would gather, gossip, and party with alcohol. On occasion, during the day, she and a couple of her friends would go to the local cukrárna (pastry shop) for some gossip over a piece of pastry and mineral water. On a rare occasion, she and her friends would venture out for an evening to the café Luxor at Grösslingová 5 street to listen to live music, sip on some mineral water, enjoy some koláčiky, and await an invitation to dance. During the summers of 1939 and 1940, the Reichsfelds would make short visits to the Gorábors in Hradište pod Vrátnom. And on a rare occasion, Berthold would take the family to Vienna by train to attend a theater performance. However, by September 1940, Slovak Jews had to surrender their passports to government officials (Law number 215/1940), and were prohibited from driving motor vehicles (Law number 216/1940). These were very scary and uncertain times for the Reichsfelds. Any punctuated moment of enjoyment helped ease the stress of the growing threat engulfing them.

[1] Hviezdoslavovo námestie – an historic square in the old city near Bratislava Castle, the Danube River, and the Jewish Quarter. The square is named after the Slovak poet, dramatist, translator, and member of the Czechoslovak parliament Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav. On the square were the historic Carlton Hotel where many famous and important people stayed while visiting Bratislava, as well as the Neo-Renaissance building Slovak National Theater (known as Mestské Divadlo [City Theater] or Stadttheater in the 1930s), the home of the oldest Slovak professional theater (1886) consisting of three ensembles (opera, ballet, and drama). The multistory building where the Reichsfeld’s apartment was located on the square was owned by Dr. Rival, a Jewish physician serving in the Czechoslovak Army as chief of medicine at the military hospital in Bratislava. He also had a business on the side as landlord and owner of the large apartment building on the famous square. Berthold met Dr. Rival while communing with fellow Jews at the Bratislava Neolog synagogue on Staromestská street in the Jewish Quarter directly under the Bratislava Castle (Podhradie) next to the famous St. Martin's Cathedral (the coronation church of 11 kings and queens plus 8 of their consorts between 1563 and 1830, including that of Maria Theresa of Austria) and just around the corner from Hviezdoslavovo námestie. When the Second World War broke out, Slovak Jewish physicians were among the last Jews to lose their jobs, particularly in Bratislava where the military hospital was located. However, once Dr. Rival’s Jewish work permit under Slovak law was revoked, he was removed from his official position. Dr. Rival had a daughter and son. The son, Ján, was five years younger than Georgina. He managed to survive the war and complete his medical studies at Bratislava’s Faculty of Medicine at Comenius University in 1959. He emigrated to the U.S. during the Prague Spring in 1968. In 1969, he joined the staff of Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, Michigan, where he practiced as an internist and eventually became chief of the department of internal medicine. At one time, he was also governor of the Michigan Chapter of the American College of Physicians. Dr. Rival’s daughter won the rare permission from Slovak Fascist authorities during the war to remain living at her family’s home in the apartment building on Hviezdoslavovo námestie. Most Jews in Bratislava at the time not only lost all their possessions, employment, and civil rights, they also were deported to extermination camps in Poland.

[2] In the early 1920s there were approximately 11,000 Jews in Bratislava: 3,000 Neolog and 8,000 Orthodox. In the 1930s there were 14,882 Jews in the city (12% of the total population).

[2] In the early 1920s there were approximately 11,000 Jews in Bratislava: 3,000 Neolog and 8,000 Orthodox. In the 1930s there were 14,882 Jews in the city (12% of the total population).

|

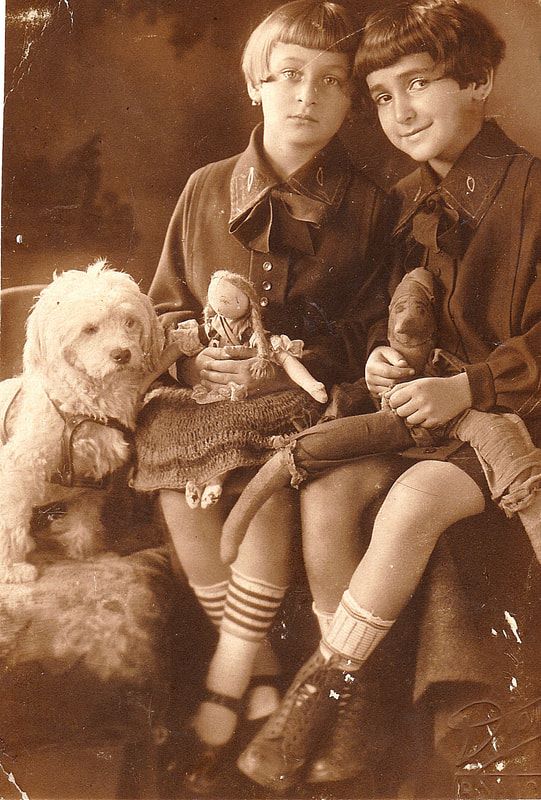

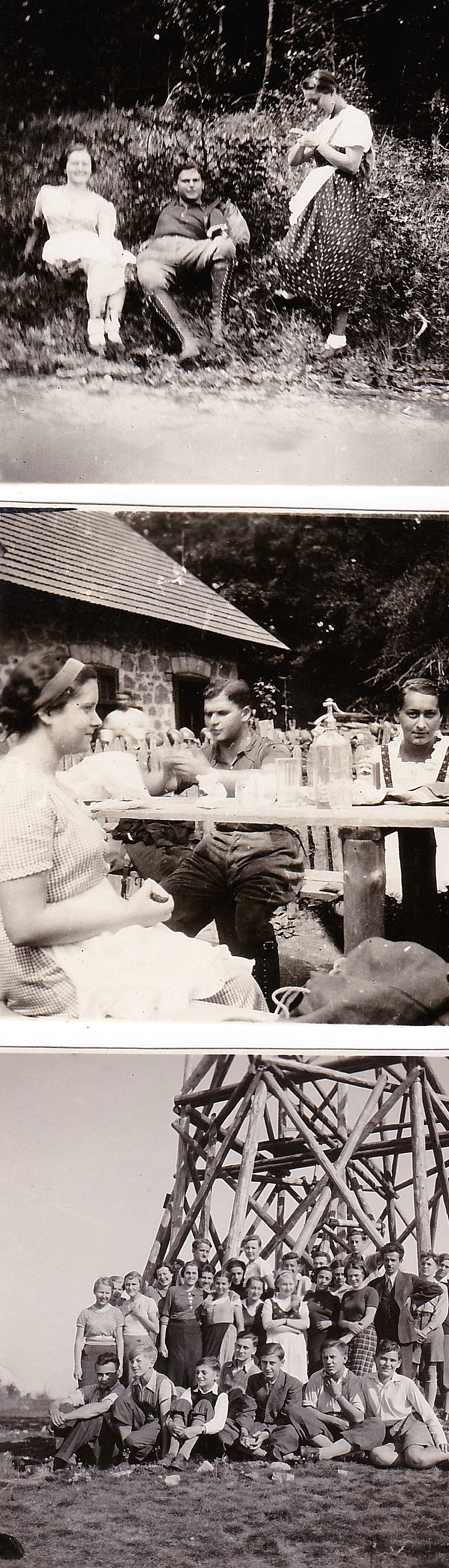

Her summer vacations were usually spent at Hradište pod Vrátnom with her Aunt Janka (Berthold’s older sister), Uncle Bernát Goráber, and her two cousins Hela and Józef. She dearly loved the little village, located in a deep valley in the western Carpathian Mountains, just west of Trnava. Tall granite peaks enclosed the rich, moist, green valley. The meadows and pastures surrounding the village reached out in all directions to meet forests of beech, oak, and pine that climbed the mountain slopes. Down the side of one mountain crawled a clear, cold, rock-strewn brook, which crossed the meadows and passed through the village on its way southward. In the fresh, vibrant air, half-naked boys gathered beside the stream to fish for trout or hunt for crabs that lay hidden among the willow tree roots in the shadowy waters. Patches of mountain flowers colored the fields and mingled with the verdant grass. Young girls often wandered happily in the warm summer sun across these fields, collecting fragrant bouquets of daisies, bluebells, and Forget-Me-Nots (Vergissmeinnicht). Sometimes, they would stop to rest on the grass and weave lovely garlands of flowers for their heads. Or, they would stretch out on the cool, damp ground and lazily watch the clouds drift by. In this carefree setting Georgina passed her summer holidays, content with her surroundings. Her cousin, Hela, and her aunt and uncle were Georgina’s friends, and she was happy here. Hradište pod Vrátnom was her second home.

The Gorábers owned and managed the only general store in the village. It provided the village farmers with whatever necessities, and a few luxuries as well, they could not themselves provide on their small farms. It was also a collection agency for local handicraft work that her aunt bought from the village women and sold throughout Europe and even in America. Georgina loved to sell candy and pretty ribbons from behind the counter during those hours when she wasn’t off in the meadows or down at the stables with the farmers at milking time. |

Best of all for Georgina, the village store was a social center, where the farmers would gather after the day’s work had ended. The men and women would drop by to visit with friends and exchange the news of the day. Girls and boys would sit out on the stairs at the entrance to the store and talk and giggle and sing. Boys strutted in manly fashion before innocent girls who blushed and whispered secretly, for they knew the boys sought to impress them. Sometimes the village youth teased Georgina because she was a city girl who never tired of catching frogs and mice for pets. She would bathe her captives, feed them generously, give them abundant love, and then set them free again. These were gentle days which she would remember always.

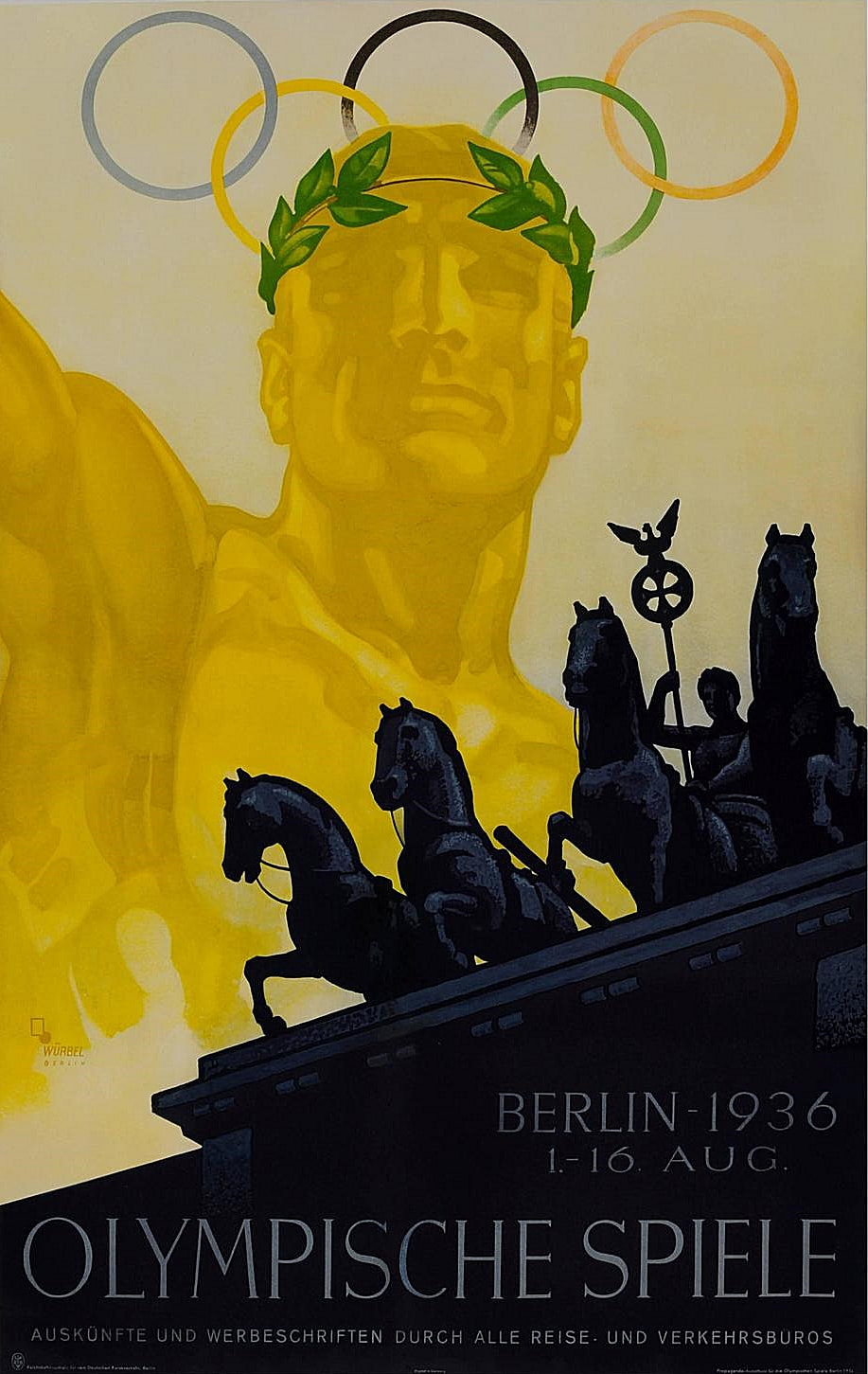

Berlin Olympics

1936

1936

|

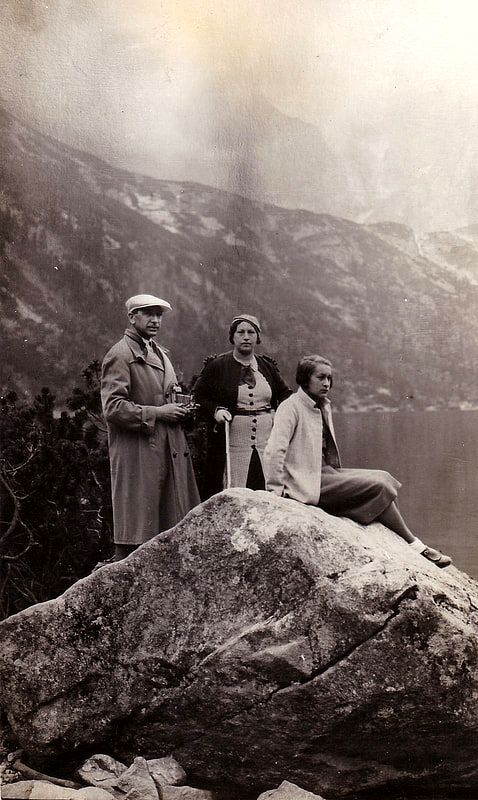

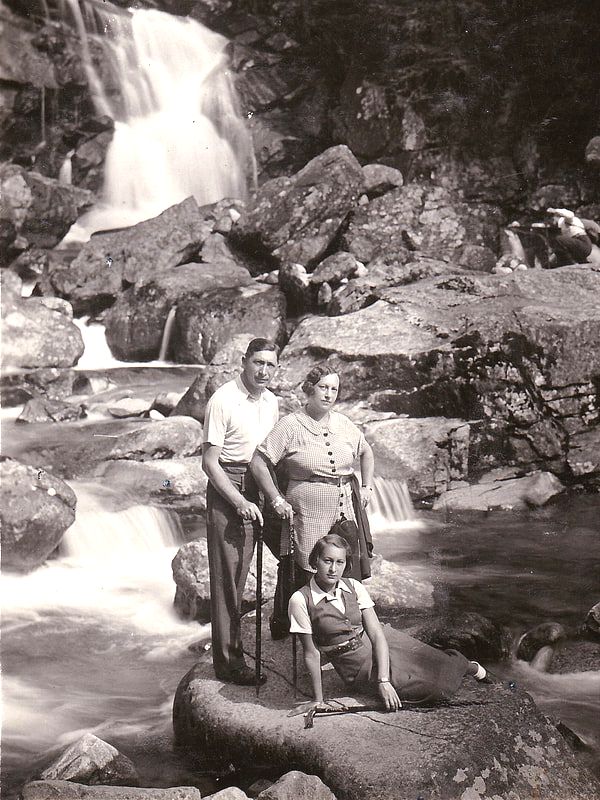

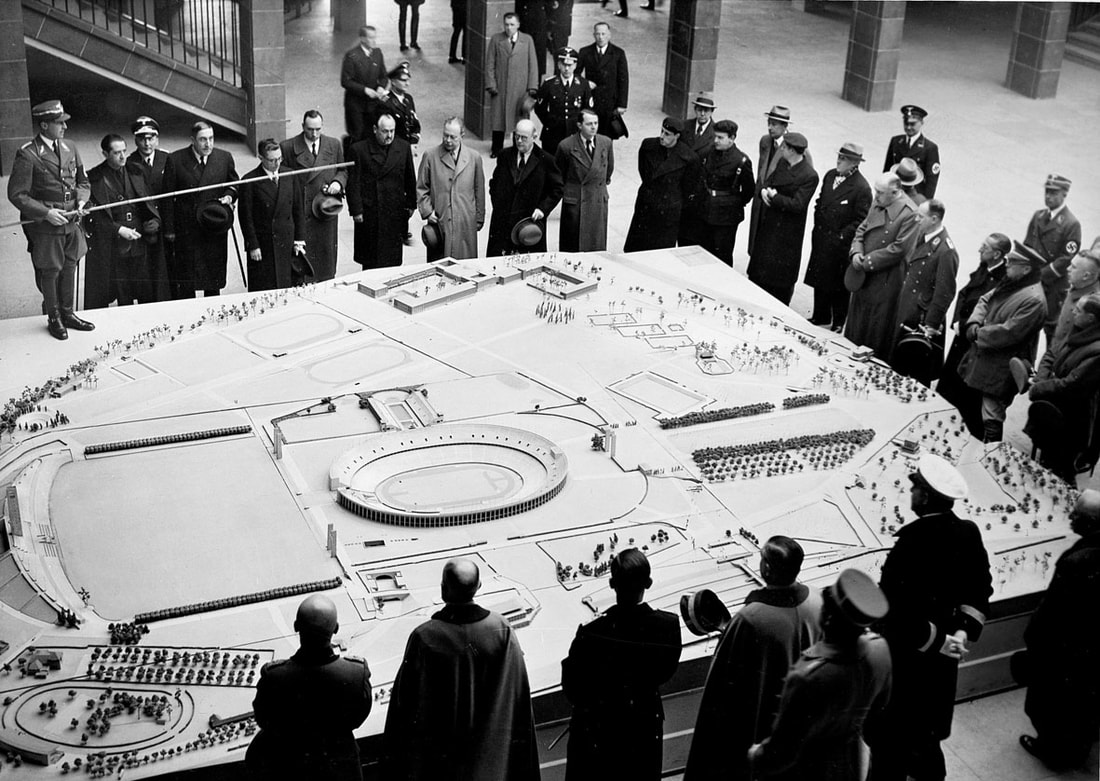

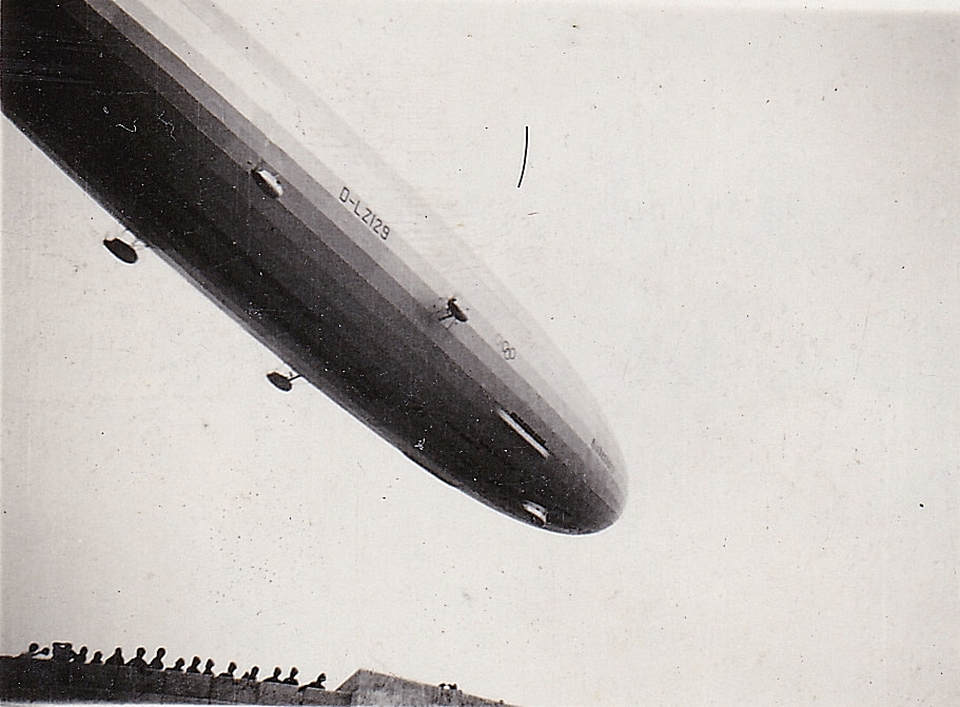

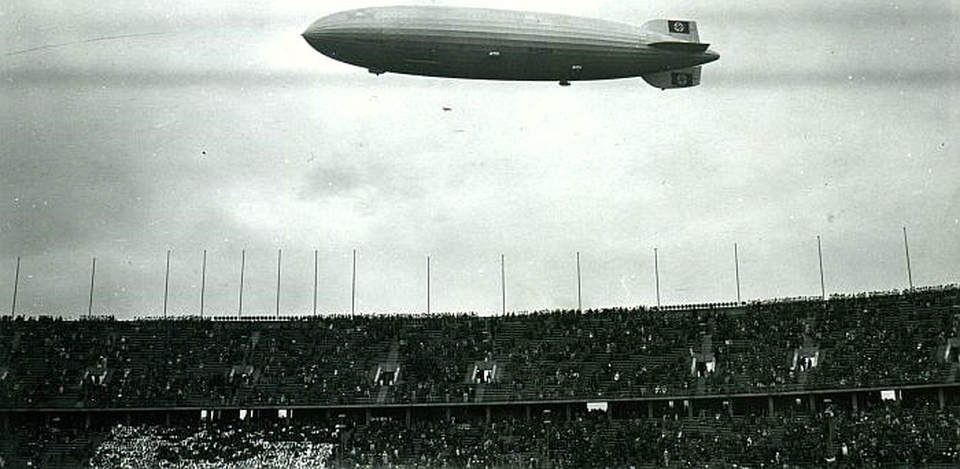

In the summer of 1936, Georgina and her parents traveled to Berlin, Germany along with Georgina's cousin Helena Goraber to attend the XI Olympiad and travel through Europe. They boarded a train in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia and rode through Prague and on to Berlin. In Berlin, they had prearranged accommodations with a private family to stay in their home. Berthold discovered at a local railroad station in Bratislava a posted announcement of the availability of some rooms in the private Berlin home. Upon their arrival in Berlin they took a taxi to the private home where the owners welcomed and hosted them.

During the Berlin Olympics, Georgina and her family witnessed many historic events and visited many historic sites. On several occasions, they saw Reichs Chancellor Adolf Hitler and his closest associates in the Nazi regime. They witnessed the historic achievements of American Olympic Champion Jesse Owens and other Olympic athletes. The Reichsfelds remained in Berlin and attended the Olympic events for several days, toured Berlin, and then proceeded on their European vacation, first to Potsdam, Germany, then Warnemünde seaside resort in Rostock, Germany on the Baltic Sea, and finally Copenhagen, Denmark. From Denmark they returned home to Bratislava, Czechoslovakia. |

At the time of the Berlin Olympics, few living outside Germany recognized and really understood the gathering storm that was approaching over the horizon of the European continent. However, the signs were clearly evident to the Germans who already by 1936 witnessed the following foretelling political developments in Germany:

- 30 January 1933: Adolf Hitler named Chancellor of Germany as his National Socialist German Workers Party (NAZI) assumes control of the German state.

- 27 February 1933. Arson of the Reichstag building of the German Parliament setting the stage for the Reichstag Fire Decree suspending of most rights guaranteed under the 1919 Weimar Constitution, allowing the Nazis to arrest communists and increase police action throughout Germany.

- 22 March 1933. The SS (Schutzstaffel) establishes the Dachau concentration camp for political prisoners in southern Germany.

- 1 April 1933. Members of the Nazi Party and its affiliated organizations organize a nationwide boycott of Jewish-owned businesses in Germany.

- 7 April 1933. The German government issues the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service (Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums), which excludes Jews and other political opponents of the Nazis from all civil service positions and disbarment of non-“Aryan” lawyers by 30 September 1933.

- 25 April 1933. The German government issues the Law against Overcrowding in Schools and Universities, which dramatically limits the number of Jewish students attending public schools to five percent of total student population.

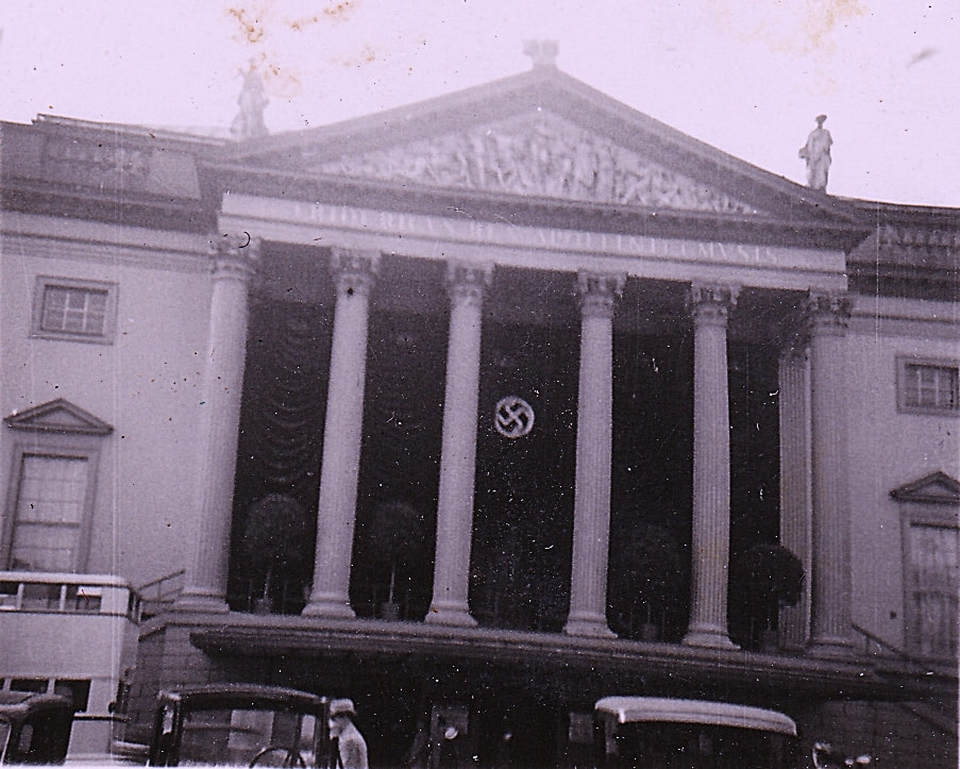

- 10 May 1933. German university students burn upwards of 25,000 “un-German” books in Berlin’s Opera Square (Opernplatz). Some 40,000 people gather to hear Reichs Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels deliver a fiery address: “No to decadence and moral corruption!”

- 14 July 1933. The German government passes the “Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases” (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses), mandating the forced sterilization of certain individuals with physical and mental disabilities, as well as sterilization of Roma (Gypsies), “asocial elements," and Afro-Germans.

- 4 October 1933. The German government passes The Editors Law (Schriftleitergesetz) forbiding non-“Aryans” to work in journalism.

- 24 November 1933. The German government passes the “Law against Dangerous Habitual Criminals.” The new law allows courts to order the indefinite imprisonment of “habitual criminals” if they deem the person dangerous to society. It also provides for the castration of sex offenders.

- 2 August 1934. German President Paul von Hindenburg dies. With the support of the German armed forces, Hitler becomes President of Germany. On 19 August 1934, Hitler abolishes the office of President and declares himself Führer of the German Reich and People, in addition to his position as Chancellor. In this expanded capacity, Hitler now becomes the absolute dictator of Germany; there are no legal or constitutional limits to his authority.

- 15 September 1935. The German parliament (Reichstag) passes the Nuremberg Race Laws laying the foundation for and legalizing much of what was to engross most of Europe in the 1940s and concluding with the Final Solution to the Jewish Question (die Endlösung der Judenfrage).

- June 1936. The SS establishes the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienberg (35 km north of Berlin).

Although, in hindsight it was bold of the Reichsfelds to visit Germany in August 1936, like many Jews of the time, they failed to grasp the growing danger in their midst.

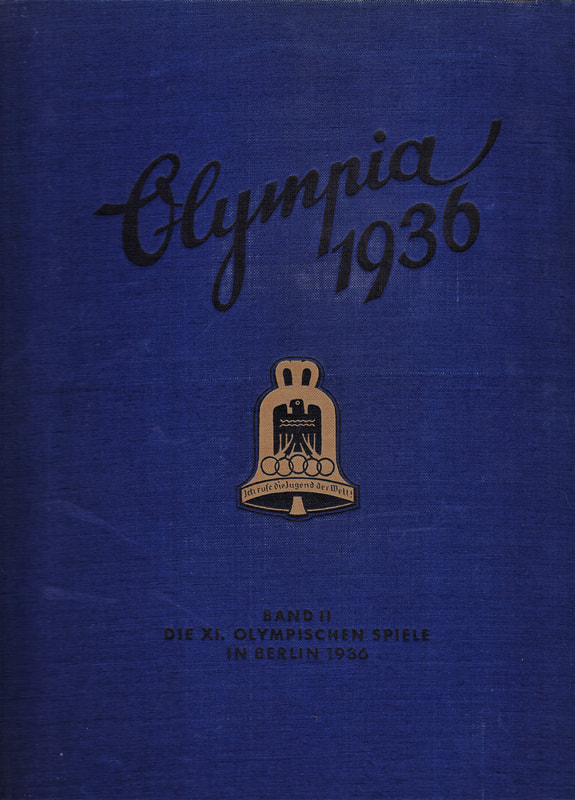

The Reichsfelds purchased the official two-volume album set of the XI Olympiad, published by the German Olympic Committee in 1936. The motto on the Olympic Bell is: "Ich rufe die Jugend der Welt!" (I call the youth of the world!).

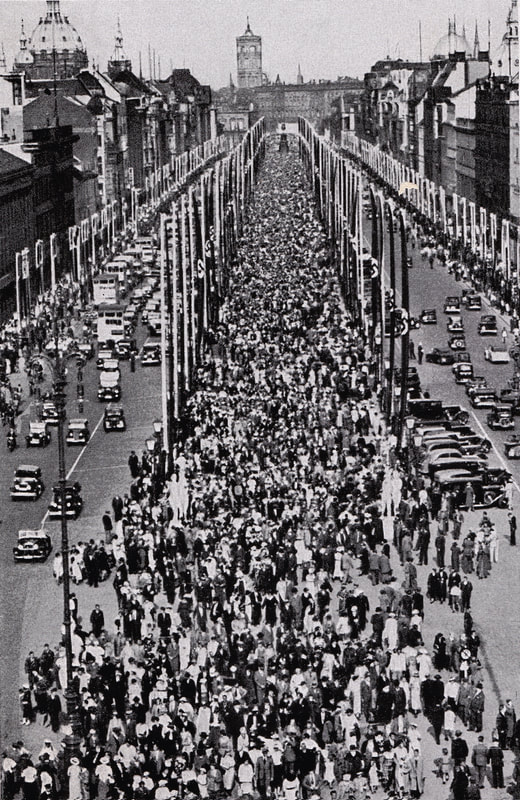

1 August 1936, Adolf Hitler rides in a motorcade west through the Brandenburg Gate to the opening ceremonies of the XI Olympiad in Berlin. Unter den Linden Boulevard is visible through the gate. The Reichsfelds were present to witness Hitler's motorcade.

(Photo credit: National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD)

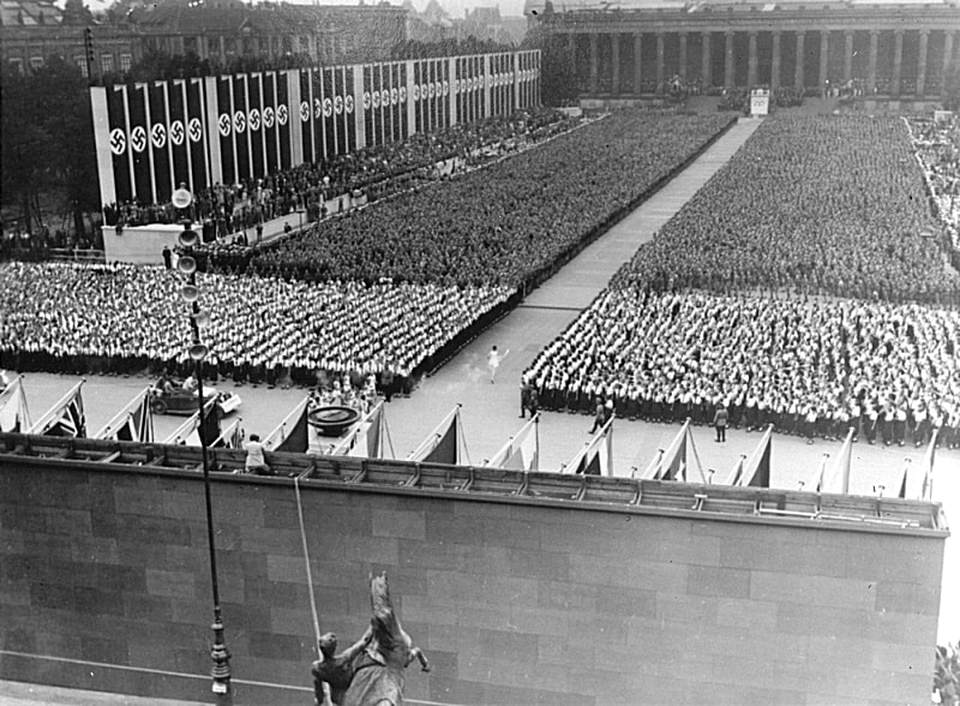

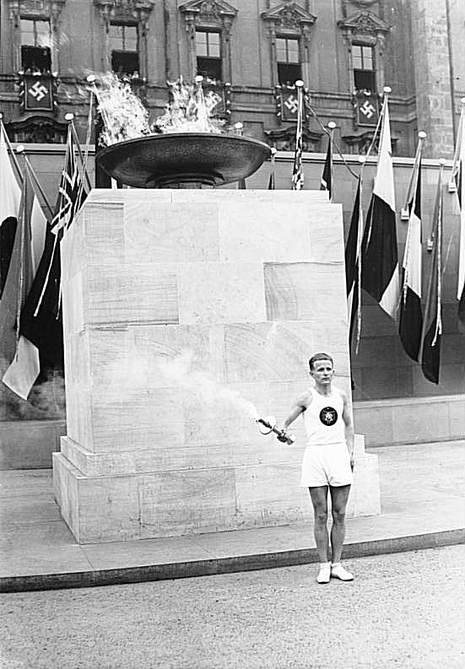

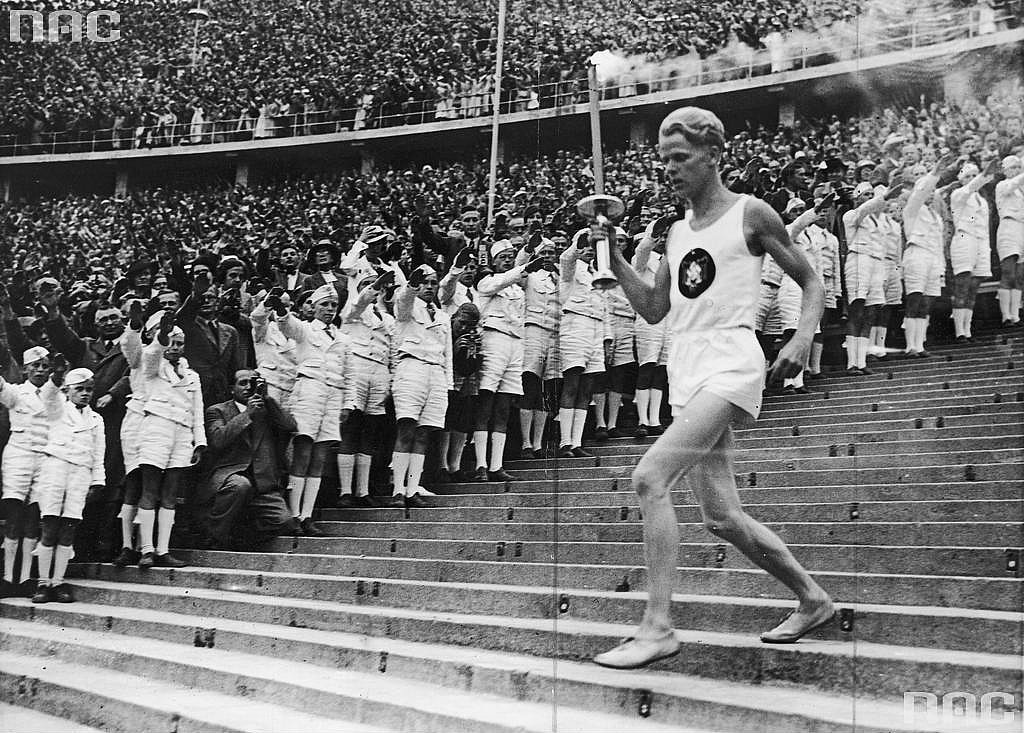

An innovation in 1936 was the Olympic torch relay, lit by the rays of the sun at Olympia in Greece and carried by over 3,000 relay runners to the Olympiastadion in Berlin. In all, the torch was transported over 3,187 km by 3,331 runners in 12 days and 11 nights from Greece to Berlin. It is a tradition that has continued at every subsequent Olympic Games. The last of the relay runners lit the Olympic cauldrons in central Berlin and the Olympic Stadium. These photographs show the lighting of the two cauldrons on Unter den Linden Boulevard at 12 noon on the opening day of the games by 26-year-old 400-meter runner Siegfried Eifrig. Eifrig sprinted 1,500 meters east on Unter den Linden from in front of the Soviet Embassy (Nos. 63-65 at the southeast corner of Wilhelmstraẞe and Unter den Linden), past the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great, crossing the Spree River over the Schlossbrücke bridge, turning north into Lustgarten where he lit the cauldron in front of the Altes Musuem. He then proceeded to light the cauldron on Unter den Linden Boulevard directly opposite Lustgarten and in front of the Stadtschloss.

|

The flame at Lustgarten served as the starting point for the final 12.5 km relay to Olympiastadion for the opening ceremonies four hours later at 1600 hours. The final relay team lit a torch in the cauldron in Lustgarten and began their trek westward down Unter den Linden Boulevard (north traffic lane), past the statue of Frederick the Great, under the Brandenburg Gate, through Hindenburg Platz, Charlottenburger Chaussee, Bismarckstraẞe, Kaiserdamm, Adolf Hitler Platz (now Theodor Heuss Platz), Reichsstraẞe, Olympische Straẞe, Olympischer Platz (north traffic lane), to the eastern Olympic Gate. Fritz Schilgen, a three-time 1500-meter champion, awaited at the eastern Olympic Gate to carry the Olympic Torch the final 500 meters. As the last strains of Strauss’s composition faded in the stadium, cheers were heard from outside when the torch bearer passed the burning torch to Schilgen. He then proceeded between the two stone pillars at the eastern gate on to the entrance to Olympiastadion where he paused for a moment at the gap at the top of the stairs as the crowd gasped and then fell silent. He descended the eastern steps into the arena, ran 200 meters counter-clockwise along the southern running track to the western gate where he climbed the Marathon Steps to light the Olympic Cauldron to signify the formal commencement of the XI Olympiad.

|

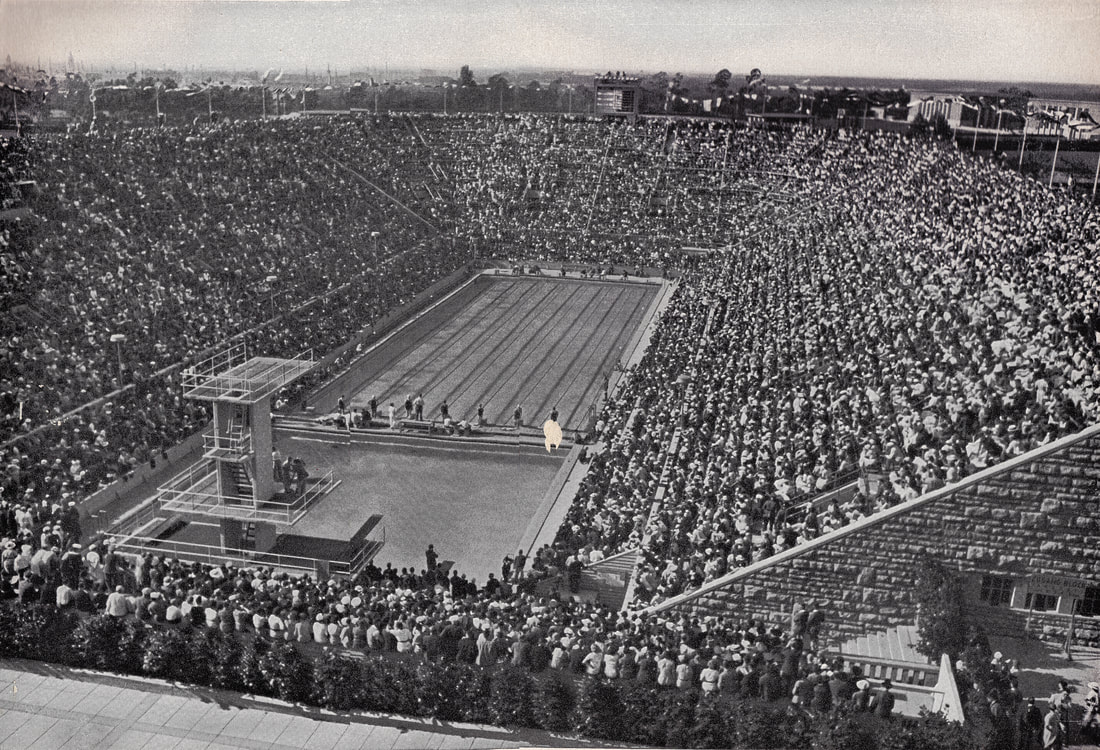

Olympiastadion stands 12.5 km west of Lustgarten outside central Berlin.

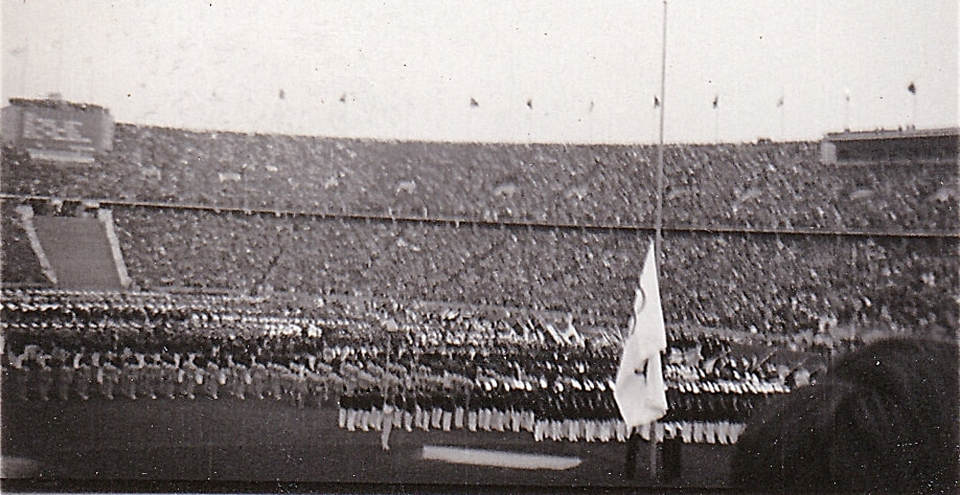

1 August 1936. Opening ceremonies to the Games of the XI Olympiad

From the west entrance and descending the Marathon stairs to the stadium, Count Henri II de Baillet-Latour–President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC)–walking just ahead of Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler along with Dr. Theodor Lewald–Ceremonial President of German Olympic Organizing Committee and Secretary of IOC–walking to right of and behind Hitler.

(The Reichsfeld's seats were located in the top right corner of the above photograph.)

From the west entrance and descending the Marathon stairs to the stadium, Count Henri II de Baillet-Latour–President of the International Olympic Committee (IOC)–walking just ahead of Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler along with Dr. Theodor Lewald–Ceremonial President of German Olympic Organizing Committee and Secretary of IOC–walking to right of and behind Hitler.

(The Reichsfeld's seats were located in the top right corner of the above photograph.)

1 August 1936. Opening ceremonies to the Games of the XI Olympiad in Olympiastadion. Indian delegation entering via the tunnel under west Marathon gate. The Reichsfelds' seats during the opening ceremonies were just north of the west Marathon gate tunnel down close to the field, as seen in the above photograph.

Above: Czechoslovak delegation and athletes entering Olympiastadion along south side of oval track

1 August 1936. Olympic Torch bearer Fritz Schilgen pausing at the top of east entrance stairs as the crowd salutes. Directly below Schilgen on the field stands the German delegation in white next to the U.S. delegation.

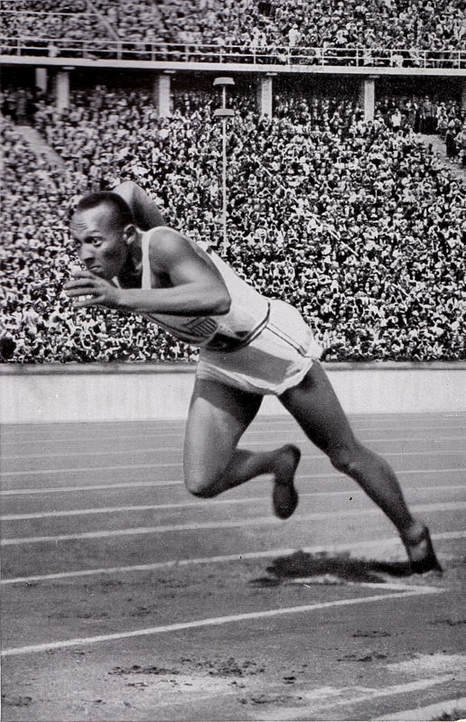

Georgina and her family witnessed the historic achievements of Jesse Owens on the field. She remembers it to this day, as it was the first time she had ever laid eyes on an American Negro. (Photos taken from her Olympic albums.)

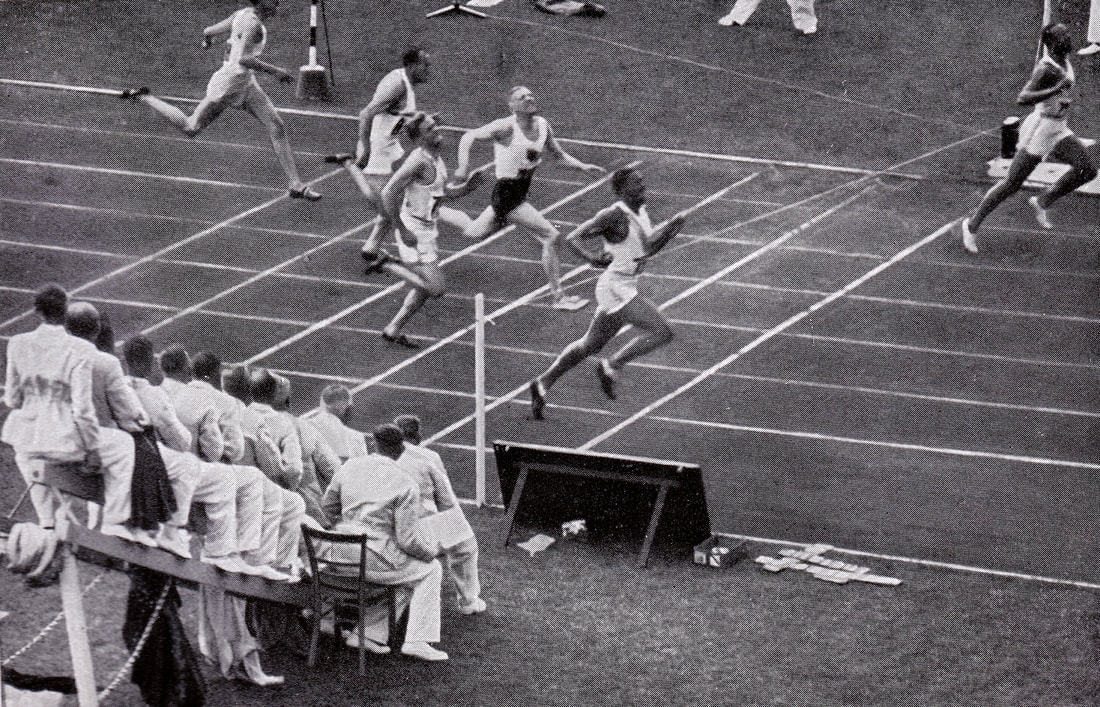

Above: starting and winning the gold in the 100-meter dash tying the world record with 10.3 seconds.

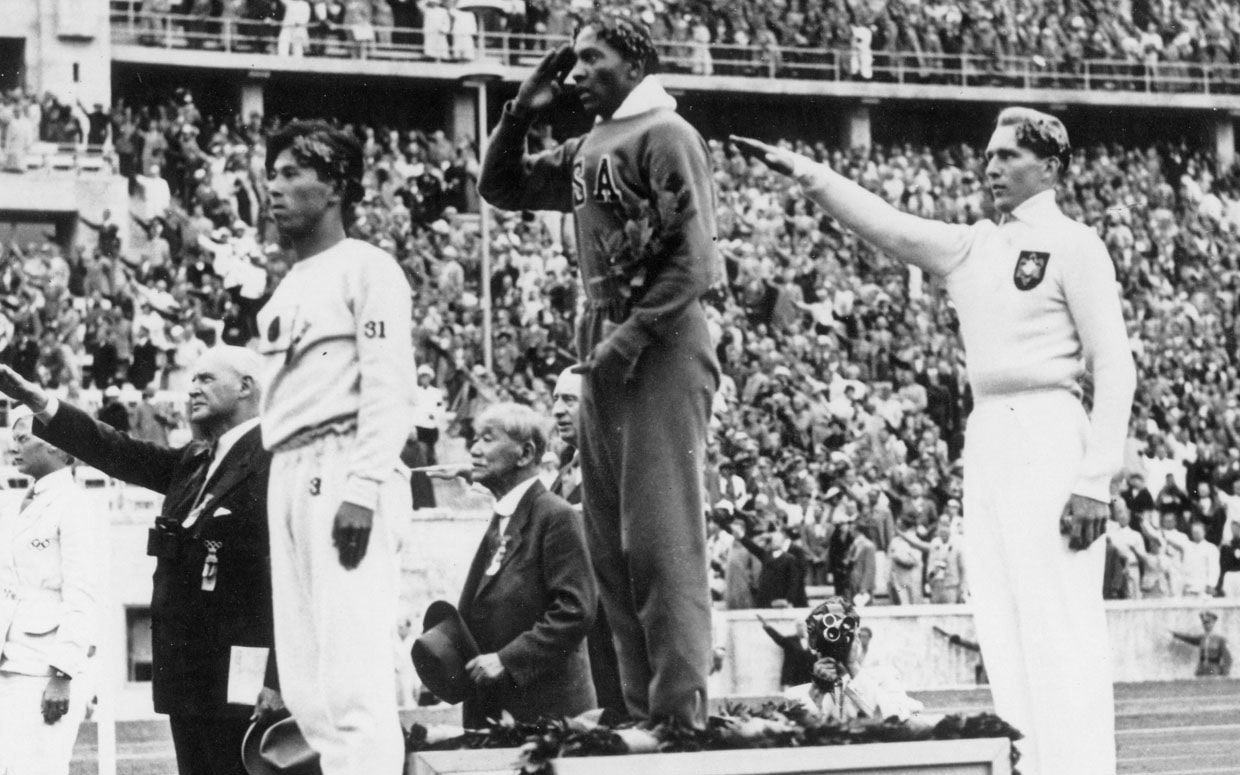

Below: Left winning the gold in the long jump with a new Olympic record of 26 feet 5 ¼ inches; Right saluting the American anthem and receiving a gold medal for the long jump (left to right: Japan's Naoto Tajima, Jesse Owens, Germany's Lutz Long). In addition to the two gold medals mentioned above, Jesse Owens won two more gold medals at the Berlin games for the 200-meter dash with a new Olympic record of 20.7 seconds and the 400-meter relay (first leg) with a new Olympic and world record of 39.8 seconds.

The long jump on August 4 was Long's first event against Owens, and Long met his expectations by setting an Olympic record during the preliminary round. In contrast, Owens fouled on his first two jumps. While speaking with Long’s son Kai, Owens admitted in 1964 that during qualifying rounds of the long jump, Lutz approached him and told him to try to jump from a spot several inches behind the take-off board to safely qualify for the finals. Owens went on to win the gold medal in the long jump with 8.06 meters while besting Long’s own record of 7.87 meters. Long won the silver medal for second place and was the first to congratulate Owens: they posed together for photos and walked arm-in-arm to the dressing room. Owens said, “It took a lot of courage for him to befriend me in front of Hitler... You can melt down all the medals and cups I have and they wouldn't be a plating on the twenty-four karat friendship that I felt for Luz Long at that moment.” Long’s competition with Owens is recorded in Leni Riefenstahl’s documentary Olympia – Fest der Völker.

Long served in the Wehrmacht during World War II. During the Allied invasion of Sicily, Long was killed in action on 14 July 1943. He was survived by two sons, Kai-Heinrich and Wolfgang. Wolfgang died at 9-months old.

Long and Owens corresponded after 1936. In his last letter, Long wrote to Owens and asked him to contact his son after the war and tell him about his father and “what times were like when we were not separated by war. I am saying—tell him how things can be between men on this earth.” After the war, Owens travelled to Germany to meet Kai Long, who is seen with Owens in the 1966 documentary Jesse Owens Returns to Berlin, where he is in conversation with Owens in the Berlin Olympic Stadium. Owens later served as Kai Long's best man at his wedding

Below: Left winning the gold in the long jump with a new Olympic record of 26 feet 5 ¼ inches; Right saluting the American anthem and receiving a gold medal for the long jump (left to right: Japan's Naoto Tajima, Jesse Owens, Germany's Lutz Long). In addition to the two gold medals mentioned above, Jesse Owens won two more gold medals at the Berlin games for the 200-meter dash with a new Olympic record of 20.7 seconds and the 400-meter relay (first leg) with a new Olympic and world record of 39.8 seconds.

The long jump on August 4 was Long's first event against Owens, and Long met his expectations by setting an Olympic record during the preliminary round. In contrast, Owens fouled on his first two jumps. While speaking with Long’s son Kai, Owens admitted in 1964 that during qualifying rounds of the long jump, Lutz approached him and told him to try to jump from a spot several inches behind the take-off board to safely qualify for the finals. Owens went on to win the gold medal in the long jump with 8.06 meters while besting Long’s own record of 7.87 meters. Long won the silver medal for second place and was the first to congratulate Owens: they posed together for photos and walked arm-in-arm to the dressing room. Owens said, “It took a lot of courage for him to befriend me in front of Hitler... You can melt down all the medals and cups I have and they wouldn't be a plating on the twenty-four karat friendship that I felt for Luz Long at that moment.” Long’s competition with Owens is recorded in Leni Riefenstahl’s documentary Olympia – Fest der Völker.

Long served in the Wehrmacht during World War II. During the Allied invasion of Sicily, Long was killed in action on 14 July 1943. He was survived by two sons, Kai-Heinrich and Wolfgang. Wolfgang died at 9-months old.

Long and Owens corresponded after 1936. In his last letter, Long wrote to Owens and asked him to contact his son after the war and tell him about his father and “what times were like when we were not separated by war. I am saying—tell him how things can be between men on this earth.” After the war, Owens travelled to Germany to meet Kai Long, who is seen with Owens in the 1966 documentary Jesse Owens Returns to Berlin, where he is in conversation with Owens in the Berlin Olympic Stadium. Owens later served as Kai Long's best man at his wedding

In addition to witnessing the exploits of Jesse Owens on the athletic field, Georgina and her family attended several other events and venues. (Photographs taken from her Olympic albums)

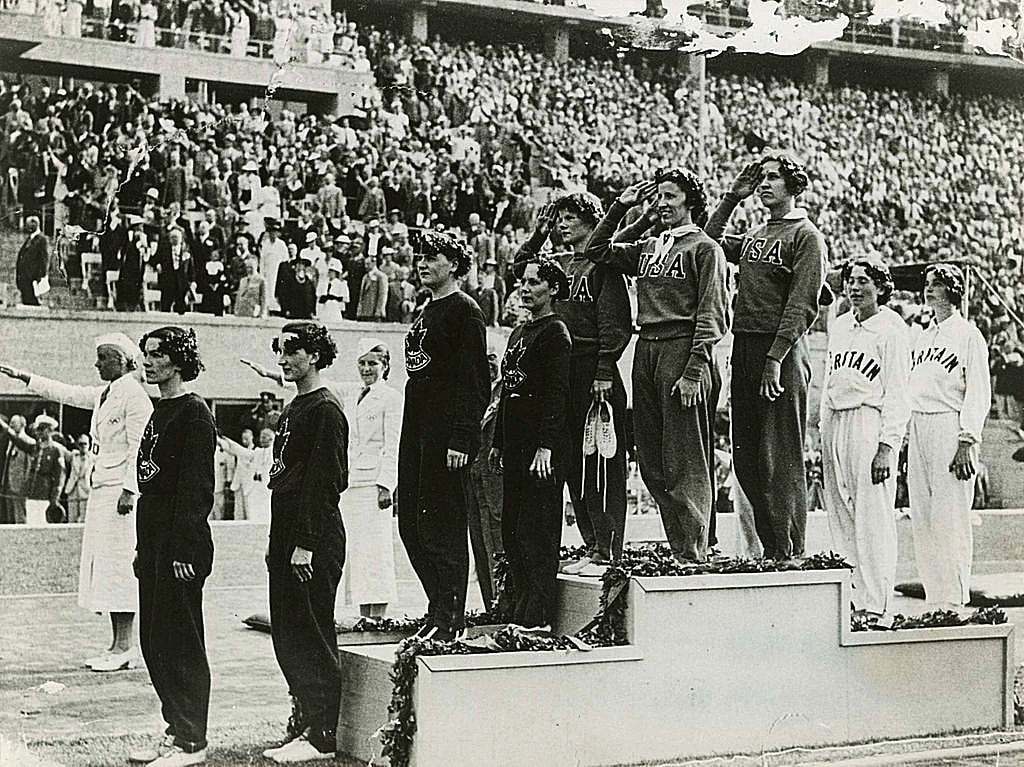

9 August 1936. "The Anglo Sweep" Women's 4 x 100-meter track relay award ceremony in Olympiastadion.

Gold – US: Harriet Bland; Annette Rogers; Betty Robinson; Helen Stephens

Silver – Great Britain: Eileen Hiscock; Violet Olney; Audrey Brown; Barbara Burke

Bronze – Canada: Aileen Meagher; Hilda Cameron; Mildred Dolson; Dorothy Brookshaw

Gold – US: Harriet Bland; Annette Rogers; Betty Robinson; Helen Stephens

Silver – Great Britain: Eileen Hiscock; Violet Olney; Audrey Brown; Barbara Burke

Bronze – Canada: Aileen Meagher; Hilda Cameron; Mildred Dolson; Dorothy Brookshaw

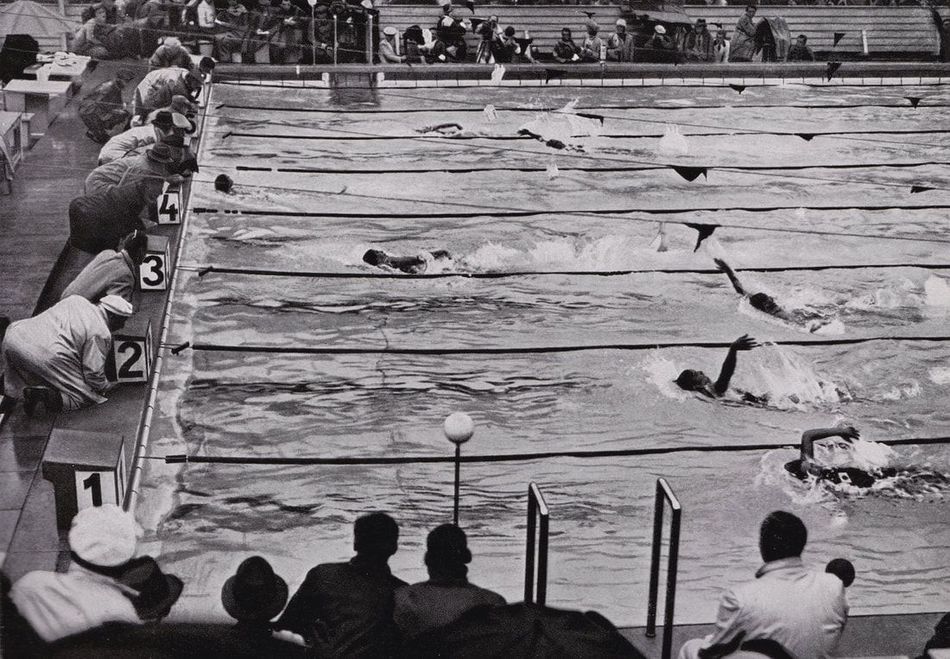

On 14 August, 18-year-old American swimmer Adolph Kiefer won the gold medal in the men’s 100-meter backstroke (lane 5, above). He set new Olympic records in the first-round heats (1:06.9), the second-round heats (1:06.8), and the event final (1:05.9). His Olympic Record would stand for over 20 years, finally broken by David Theile in the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Australia.

Berlin Unter den Linden Straße

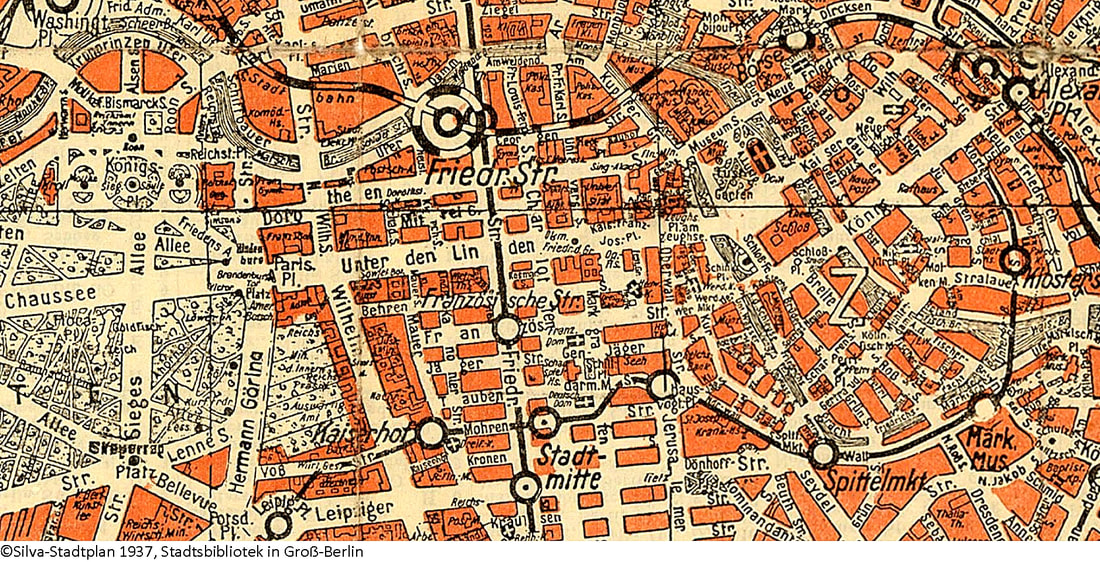

The map above focuses on the historic section of central (Mitte) Berlin that Georgina and her family visited during their stay in August 1936. Most of the photographs shown below are from this district. Unter den Linden Straẞe is seen in the center of the map running from Brandenburg Gate on the west (where Pariser Platz meets Hermann Gὄring Straẞe) to the City Palace (Stadtschloss) in the east. West of the Brandenburg Gate, Unter den Linden changed to Charlottenburger Chaussee—but in 1953, West Berlin renamed the street Straße des 17. Juni (17th of June Street), to commemorate the uprising of the East Berliner workers on 17 June 1953, when the Red Army and GDR Volkspolizei shot protesting workers. From the Schlossbrücke (Palace Bridge), just east of Zeughaus, Unter den Linden changed to Kaiser Wilhelm Straẞe (now known as Karl-Liebknecht-Straße). Major north-south streets crossing Unter den Linden include (from east to west) Charlottenstraẞe, Friedrichstraẞe (abbreviated Friedr. - do not confuse with Friedr.Str. rapid rail), and Wilhemstraẞe (not to be confused with the aforementioned Kaiser Wilhelm Straẞe).

The Spree River is seen on the map snaking its way from the west, branching and turning southeast at the Monbijoustraße bridge (destroyed in 1945, rebuilt as pedestrian-only bridge in 2004) into the small Kupfergraben canal on the west and the Spree River on the east forming Museum Island (formerly known as Spree Island) and rejoining at the south end of the island at Märkischer Platz near the Waisenbrücke bridge (no longer exists). The canal and main branch of the Spree River traverse directly under many of the major historic buildings on Museum Island.

Other important landmarks to note on this map (from east to west) are: the Lustgarten complex (bordered by Berlin Cathedral on the east and Altes Museum on the north) on Museum Island on the north side of Kaiser Wilhelm Straẞe just east of the Schlossbrücke (Palace Bridge); Stadtschloss (City Palace) directly south across the street from Lustgarten with the semi-circular National Kaiser Wilhelm Monument sitting on the east bank of the Kupfergraben canal; Opernplatz (abbreviated Op.-Pl S.) on the south side of Unter den Linden and just east of Charlottenstraẞe; the equestrian statue of Frederick the Great (abbreviated on the map as Okm. Friedr.d.Gr.) on Unter den Linden just east of Charlottenstraẞe; Pariser Platz (abbreviated Paris. Pl.) just west of Wilhemstraẞe; Brandenburg Gate just west of Pariser Platz on the east side of Hermann Gὄring Straẞe; and the infamous Reichstag building north of Brandenburg Gate on the northwest corner of Hermann Gὄring Straẞe and Dorotheenstraẞe at the east end of Kὄnigsplatz and on the left bank of the Spree River that bends northward here. These are all important landmarks and geography to familiarize yourself with in order to better understand the following photographs. Everything on this map lying east of the Brandenburg Gate and the Reichstag building ended up behind the Berlin Wall belonging to East Berlin and the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR) after the war (see: Berlin Wall). (Note: the geography, street names, and many of these landmarks are no longer seen on modern maps of Berlin.)

|

These historic pre-war views of central Berlin at the time of the Summer Olympics present a sobering prelude of what was soon to come to Berlin. Many of these buildings photographed here by Georgina during her visit in August 1936 were destroyed during Allied bombings beginning in 1943 and throughout the latter portion of the war, and during the final battle of Berlin.

Unter den Linden Straẞe was and remains one of Europe's most famous boulevards in historic Mitte Berlin. Composer Johann Strauss III wrote the waltz “Unter den Linden” in 1900 commemorating the cultural importance of this boulevard. Running from the City Palace (Stadtschloss) to Brandenburg Gate, it is named after the linden trees that have lined the pedestrian mall on the median and the two broad carriageways since 1647. The avenue links numerous historic Berlin sights, landmarks, and river tours. Since 1937, the numbering of the properties on the street has started on the east end with the Zeuhaus just west of the Schlossbrücke (Palace Bridge), which connects Unter den Linden with the Lustgarten and Museum Island. In the course of the building of the north-south tunnel for the rapid-transit train in 1934–35, most of the linden trees were cut down and during the last days of World War II the remaining trees were destroyed or cut down for firewood. The present-day linden trees were replanted in the 1950s. |

Just to the south of the statue of Frederick the Great lied the historic Altes Palais (Old Palace), No. 9 on the Boulevard, the favorite residence of Emperor Wilhelm I (rebuilt after the war and now the Alte Bibliothek of the Humboldt University law faculty). Adjacent to and directly east of the palace lied the Opernplatz (now known as Bebelplatz). Opernplatz, a public square bordered by the Staatsoper (Berlin State Opera House) on the east, Altes Palais on the west and by St. Hedwig's Cathedral (the first Catholic church built in Prussia after the Reformation), was where on 10 March 1933, the nationalist German Student Association hosted the infamous bücherverbrennung (book burning) of 25,000 books considered subversive or representing ideologies opposed to Nazism. There, some 40,000 people heard Reich's Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels deliver a fiery address: "No to decadence and moral corruption!" Goebbels enjoined the crowd. “Yes to decency and morality in family and state!"

Further east from the Altes Palais on Unter den Linden Boulevard is the Schlossbrücke (Palace Bridge), which connects Unter den Linden with Museum Island (named for the complex of internationally significant museums on the northern half of an island in the Spree River in the central district of Berlin on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites). On the north side of Unter den Linden just east of the Palace Bridge lied the Lustgarten (Palace Garden). The Lustgarten is bordered on the east by The Berlin Cathedral (Berliner Dom, officially known as the Evangelical Supreme Parish and Collegiate Church) and on the north by the Altes Museum (Old Museum). The Altes Museum was and remains world-renowned for its extraordinary collection of classical antiquities (Egyptian, Etruscan, Roman, and Greek), many of which the Russians pilfered and transported to Russia via Soviet Trophy Brigades where they are currently on display in museums throughout the country. Among the looted artifacts was the legendary Priam's Treasure from the lost city of Troy discovered by German archeologist Heinrich Schliemann in 1837. During the war, the treasure was removed to a bunker under the Berlin Zoo where it remained until 1945. The treasure was secretly removed to the Soviet Union by the Red Army. During the Cold War, the government of the Soviet Union denied any knowledge of the fate of Priam’s Treasure. However, in September 1993 the treasure turned up at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. The return of items taken from German museums has been arranged in a treaty with Germany but, as of January 2010, is being blocked by museum directors in Russia. They are keeping the looted art, they say, as compensation for the destruction of Russian cities and looting of Russian museums by Nazi Germany in World War II. A 1998 Russian law, the “Federal Law on Cultural Valuables Displaced to the USSR as a Result of the Second World War and Located on the Territory of the Russian Federation,” legalizes the looting in Germany as compensation and prevents Russian authorities from proceeding with restitutions.

During World War II, the Altes Museum suffered significant damage and burned out almost completely when a fuel truck exploded in front of the museum, and the frescoes designed by Schinkel and Peter Cornelius, which adorned the vestibule and the back wall of the portico, were largely lost. After the war, only a portion of the damage was restored.

During the years of the Weimar Republic, the Lustgarten was frequently used for political demonstrations. The Socialists and Communists held frequent rallies there. In August 1921, 500,000 people demonstrated against right-wing extremist violence. After the murder of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau, on 25 June 1922, 250,000 protested in the Lustgarten. On 7 February 1933, 200,000 people demonstrated against the new Nazi Party regime of Adolf Hitler; shortly afterwards public opposition to the regime was banned. Under the Nazis, the Lustgarten was converted into a site for mass rallies. In 1934, it was paved over and the equestrian statue of Friedrich Wilhelm III was removed by the Nazis (in 1944 melted down for war materiél). Hitler addressed mass rallies of up to a million people there. By the end of World War II, the Lustgarten was a bomb-pitted wasteland. Located in the new East Germany, the German Democratic Republic (DDR) left Hitler’s paving in place, but planted linden trees around the parade ground to reduce its militaristic appearance. The whole area was renamed Marx-Engels-Platz. Since the reunification of Germany in 1990, the Lustgarten was in 1998 finally restored to a park and once again features fountains in the heart of Berlin.

On the south side opposite Lustgarten lied the Stadtschloss (City Palace). The Stadtschloss, originally built in the 15th century, was a royal and imperial palace, and served as the winter residence of the Electors of Brandenburg, the Kings of Prussia, and the German Emperors. During World War II, the Stadtschloss was twice struck by Allied bombs: on 3 February and 24 February 1945. On the latter occasion, when the air defense and fire-fighting systems of Berlin had been destroyed, the building was struck by incendiaries, lost its roof, and was largely burnt out; the external structure remained intact. The building was used for a 1950 Soviet war film (“The Fall of Berlin”) in which the Stadtschloss served as a backdrop, with live artillery shells fired at it for the realistic cinematic impact. The East German communist regime then leveled the ruins in late 1950. The palace is currently being rebuilt with completion expected in 2019.

c. 1900 Panoramic view of Altes Museum (left), Berlin Cathedral, Lustgarten, Schlossbrücke (Palace Bridge), and northwest corner of Stadtschloss off the Kupfergraben canal with backside view of National Kaiser Wilhelm Monument. The National Kaiser Wilhelm Monument was dedicated to Wilhelm I, first Emperor of a unified Germany. It rested on the Kupfergraben canal opposite the west main entrance to the Stadtschloss from 1897 through 1950. East German communists destroyed the monument along with the remains of the Stadtschloss in 1950.

The Reichstag building (short for Reichstagsgebäude), intended to house the Imperial Diet (Reichstag) of the newly formed German Empire, is located on the east end of Königsplatz (King's Square) where the Palace of Prussian Count Atanazy Raczyński had stood since 1842. Construction of the Reichstag building began in 1884 and completed in 1894. In 1916, the iconic words Dem Deutschen Volke ("[To] the German people") were placed above the main façade of the building.

The building caught fire on 27 February 1933, under circumstances still not entirely known. This gave a pretext for the Nazis to suspend most rights provided for by the 1919 Weimar Constitution in the Reichstag Fire Decree, allowing them to arrest communists and increase police action throughout Germany. The burning of Reichstag had also created fear in the U.S. and Western Europe of the rise of Communism in Germany. This furthered the West's Policy of Appeasement towards Hitler (who had portrayed himself as anti-communist).

During the 12 years of Nazi rule, the Reichstag building was not used for parliamentary sessions. Instead, the few times that the Reichstag convened at all, it did so in the Kroll Opera House, west of the Reichstag building. This applied particularly to the session of 23 March 1933, in which the Reichstag surrendered its powers to Adolf Hitler in the Enabling Act, another step in the so-called Gleichschaltung (“coordination”). The main meeting hall of the building (which was unusable after the fire) was instead used for propaganda presentations and, during World War II, for military purposes.

The building, never fully repaired after the fire, was further damaged by air raids. During the Battle of Berlin in 1945, it became one of the central targets for the Red Army to capture, due to its perceived symbolic significance. Today, visitors to the building can still see Soviet graffiti on smoky walls inside as well as on part of the roof, which was preserved during the reconstructions after reunification.

On 2 May 1945, Red Army photographer Yevgeny Khaldei (born to a Jewish family in Yuzovka, now Donetsk, Ukraine) took the iconic photograph Raising a flag over the Reichstag showing 18-year-old Private Alexei Kovalyov from Kiev holding the Soviet flag, which symbolized the victory of the USSR over Nazi Germany (see photographs below).

The official German reunification ceremony on 3 October 1990, was held at the Reichstag building. One day later, the parliament of the united Germany would assemble in an act of symbolism in the Reichstag building. Only after a fierce debate did the German parliament (Bundestag) conclude, on 20 June 1991, with quite a slim majority in favor of moving the capital of the newly reunited Germany back to Berlin from Bonn. Reconstruction of the building was completed in 1999, with the Bundestag convening there officially for the first time on 19 April of that year.

The Victory Column, originally located in the center of Königsplatz opposite Raczyński’s palace, was built to commemorate the Prussian victory in the Danish-Prussian War. But by the time it was inaugurated on 2 September 1873, Prussia had also defeated Austria and its German allies in the Austro-Prussian War (1866) and France in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), giving the statue a new purpose. Different from the original plans, these later victories in the so-called unification wars inspired the addition of the 27-foot, 38.5-ton bronze sculpture of Victoria.

Built on a base of polished red granite, the column sits on a hall of pillars with a glass mosaic designed by Anton von Werner. The column itself consists of four solid blocks of sandstone, three of which are decorated by cannon barrels captured from the enemies of the three aforementioned wars. The fourth and highest block is decorated with golden garlands and was added in 1938–39 when the whole monument was relocated as part of the preparation of the monumental plans to redesign Berlin into Welthauptstadt Germania. Hitler’s chief architect Albert Speer relocated the column 2 km west of the Reichstag to its present site at the Großer Stern (Great Star), a large intersection in Tiergarten Park (equivalent to NY Central Park) on the city axis that leads from the former Stadtschloss (Berlin City Palace) through the Brandenburg Gate to the western parts of the city.

On 2 May 1945, Red Army photographer Yevgeny Khaldei photographed 18-year-old Red Army Private Alexei Kovalyov holding the Soviet flag over the southeast cornice of the Reichstag building before Soviet tanks completed shelling the long-abandoned building. Visible below on the corner of Hermann Gὄring Straẞe and Dorotheenstraẞe are the remains of the historic Französisches Gymnasium—a French school established in 1689 by Elector Frederick III of Brandenburg for the children of the Huguenot families who had settled in Brandenburg-Prussia by his invitation, being persecuted for their Protestant beliefs in the Catholic Kingdom of France after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by King Louis XIV in October 1685; the school was attended by an above-average number of Jewish pupils until 1938 when the Nazis expelled all Jews from academia in Germany.

During their travels in the summer of 1936, the Reichsfelds managed to visit several other European destinations, including Potsdam, Germany (35 km southwest of Berlin), and Warnemünde seaside resort in Rostock, Germany on the Baltic Sea (3 ½ to 4 hours by train from Potsdam), and Copenhagen, Denmark (220 km by Gedser-Rostock Ferry and train from Rostock, Germany).

Continuing With Georgina's Pre-War Years in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia

|

In the autumn of 1938, Georgina and her parents attended a formal Hungarian ball in Bratislava. On the same evening, a young Czechoslovak Army Lieutenant Viliam Procházka was walking near the Reprezentak building on the Danube River and noticed an attractive young woman in her evening gown enter the building with her parents to attend the ball. With peaked interest in the beautiful young woman who captured his eye, Lieutenant Procházka decided to investigate further. Although only dressed in his working officer’s uniform, he purchased entry to the ball and proceeded to search for the young woman and her family in the ballroom. Some time passed before he could locate them among the large crowd. In the meantime, Berthold Reichsfeld attempted to engage several young men inviting them to ask his daughter to dance. Lieutenant Procházka finally spotted them sitting at their table and approached the young woman and introduced himself to her and her parents. After introduction, he invited her to dance. The young couple danced the evening away. Thereafter, Villi and Jirka (Slovak version of her name) often met and courted. Eventually, Lieutenant Procházka proposed to Jirka with the permission of her father.

|

War Years

Slovakia

1939 - April 1945

Slovakia

1939 - April 1945

|

After the German Army occupied Bohemia and Moravia on 15 March 1939, Czech Lieutenant Procházka was disarmed and deported home to Prague, as many other Czechs were. Later, with the assistance of the Czech underground, he managed to escape north to Poland and eventually join the French Army to fight the Nazi occupiers of his homeland. Before his escape, Georgina and Berthold traveled to Prague to deliver an emotional farewell to her fiancé.

|

DEPORTATION & EXTERMINATION OF SLOVAK JEWS

|

Slovakia was the first Axis partner to consent to the deportation of its Jewish citizens in the framework of the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” (die Endlösung der Judenfrage) worked out by Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann at the Wannsee conference on 20 January 1942. As a matter of fact, Slovakia was the only Axis partner who as early as 1938 promised in a conference between Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring, future Slovak Deputy Prime Minister Ferdinand Ďurčanský, and future Slovak Interior Minister Alexander Mach that Jews in Slovakia would be treated in the same way as in Germany. Moreover, Slovakia was the only Axis partner that actively pushed Germany (before Germany itself was prepared to fully tackle the task) to assist in solving the Jewish question in Slovakia. From the moment of its independence from Czechoslovakia and establishment as the First Slovak Republic on 14 March 1939, Slovakia promulgated one anti-Jewish law after another progressively dismantling fundamental civil and human rights previously protected by law paving the way for genocide of nearly 90,000 Slovak Jewish citizens.

On 9 September 1941, six years after the enactment of the Nuremberg Laws, the Slovak government promulgated law number 198/1941, titled “Regarding the Legal Standing of Jews” and commonly known as the “Jewish Codex” (Židovský kódex). This 270-article, 60-page law was the first major law of its kind in Slovakia and one of the most extensive and calculated set of anti- |